TRAVIS Ortiz's Sept. 28 "Cyber criminals" opinion piece contains a couple of bad analogies that distract from the problems citizens face when it comes to laws and the Internet. The premise of the article seems to be that the Internet is some sort of place where people congregate, which is nonsense - the Internet is a communication system. The article also perpetuates the fictional concept that copyright infringement and theft are equivalent (they are not even in the same category of the law). These analogies are used to paint a picture of an entire criminal world that exists in a place called "cyberspace."

In reality, though, there is no place called "cyberspace." There is a computer network that facilitates communication on a global scale. It is a communication system that should never be forgotten or ignored because it is fundamental for understanding the deeper problems societies face surrounding the Internet.

The most prominent problems we have as a result of laws pertaining to computers and the Internet are the restrictions on what people can say and how they are allowed to say it. For Americans, this is a particularly important issue, since the right to speak freely was written into our constitution in the early years of our country.Unfortunately, those in power today do not view freedom of speech as a good thing, unless that speech furthers their financial interests, and so we now have laws that forbid the discussion or transmission of certain information on any medium. An example of such a law is the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), which forbids any dissemination of software, or even technical descriptions of software, which defeat copy-restriction technologies.

A significant effect of the greater ability to speak freely that has resulted from so many people having Internet connections has been an empowerment of individuals. Music downloading is part of that empowerment: People are no longer dependent on recording companies for their music. Copyright law, of course, is at odds with such empowerment, but copyright law was not originally designed to govern the activities of the majority of people. In its original form, copyrights were primarily a regulation on certain industries; the copyright system was envisioned in an age where the ability to make copies of a creative work quickly required special, uncommon equipment. That age ended when computers with connections to the Internet became a common household appliance.

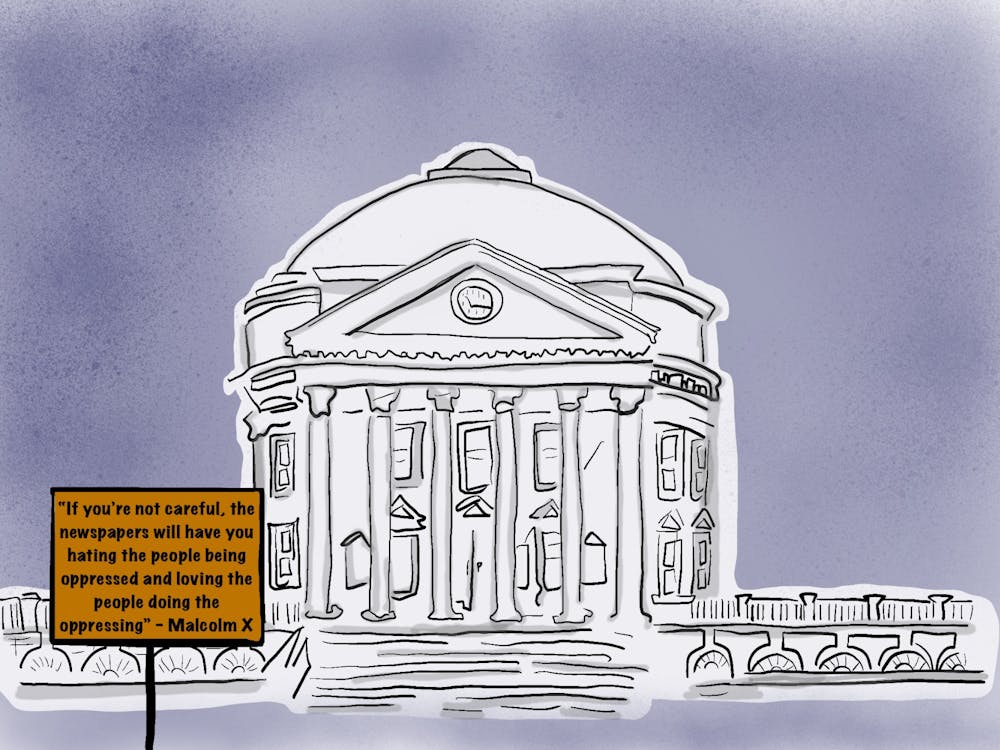

The response from Congress, under heavy lobbying pressure from the recording and movie industries (and other lesser known industries), has been to strengthen copyright law. Copyright infringement can now be prosecuted as a criminal offense, where previously it was a civil matter, if the copyright holder can convince a judge that the infringement represents a certain amount of money that was not made by legal sales, even in cases where the defendant gave away copies at no cost. The DMCA strengthened copyright law not only by directly restricting our freedom of speech, but also by creating a legal requirement for computer operators to render data inaccessible if a copyright holder claims the data infringes on their copyright. "DMCA take-downs," as they are sometimes referred to, have been used to silence criticism in the past. This strengthening of copyright law has been coupled with a propaganda campaign, which targets children from elementary school straight through high school and even in universities like this one. The message of the campaign is that copyrights are a form of property and that copyright infringement is at least as bad as stealing another person's property.

Yes, this is what is happening in the United States, and our government is pushing for other countries to do the same.

Beyond copyrights, the free speech over the Internet is threatened by increasing levels of interference by the U.S. government and large corporations.

What happened to Craigslist is an excellent example: Multiple states and the Congress pressured Craigslist to take down an entire section of its website, because people were arranging illegal activity, but law enforcement claimed it was too difficult to actually track down and catch people when they broke the law. Instead, action was taken against free speech and against a website that facilitates that speech.

Ironically, on the same day that Ortiz's column was published, the major news networks revealed that the Obama administration had submitted a bill to Congress that adds more regulations to what we are allowed to say and how we are allowed to communicate. That bill would mandate that any software or device that allows people to encrypt their communications include a "back door" for law enforcement. Effectively, the bill makes it illegal to disseminate software which lacks that back door, an immediately obvious encroachment on free speech, but the bill also attacks the ability of people to communicate privately, an issue which is intimately connected to the issue of free speech. Simply put, people are afraid to send certain messages over a public medium like the Internet without assurances that those messages will only be read by the party they intended those messages for - and that means encryption that not even law enforcement agencies can crack.

The problem is not the Internet; the Internet is, in fact, part of the solution, because of its empowering effect. The problem is the campaign to undermine our right to freedom of speech.

Benjamin Kreuter is a graduate student studying computer science.