Addressing climate change picked up bipartisan support earlier this month when the Climate Leadership Council proposed a “carbon dividend” plan — a two-piece proposal including a carbon tax and a plan to return the revenue to the population through dividends, according to The Washington Post. The group of prominent conservative thinkers includes James A. Baker, Henry Paulson, George P. Schultz, Marty Feldstein and Greg Mankiw.

According to the Carbon Tax Center, a carbon tax seeks to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by correcting the discrepancy between the market price and social cost of carbon by placing a fee on each ton of carbon dioxide.

Burning fossil fuels causes damages to the environment — including increasing global temperatures and rising sea levels — that are not reflected in its market price. Even those who don’t believe in climate change can appreciate the increases in respiratory disease, asthma and depletion in natural resources caused by increased carbon dioxide emissions.

These costs boil down to a single number — the Social Cost of Carbon. In theory, according to economics lecturer Dr. Spencer Phillips, a carbon tax bridges the gap by raising the market price to reflect the social cost. Ideally, this causes a decrease in demand for carbon-intensive goods and therein a decrease in emissions.

Many economists have advocated for a carbon tax for years, but its recent re-emergence in the political spotlight sparked new debate over its feasibility, risks and potential benefits. One of the benefits associated with a revenue-neutral carbon tax plan is its simplicity.

According to Phillips, the cap and trade system proposed in California in 2011 failed because it required the use of permits, an administration to police the trading of permits, contracts to assign emission rights and a plethora of other regulatory controls.

In addition to its simplicity, a carbon tax produces revenue that can be used in a variety of ways.

“You can give [the revenue] back as reimbursements to people of low income [or] minority groups who are suffering disproportionately from the higher cost,” fourth-year Commerce student Alexander Wolz said.

The revenue can also be reinvested into research of renewable energy to further sustainability efforts.

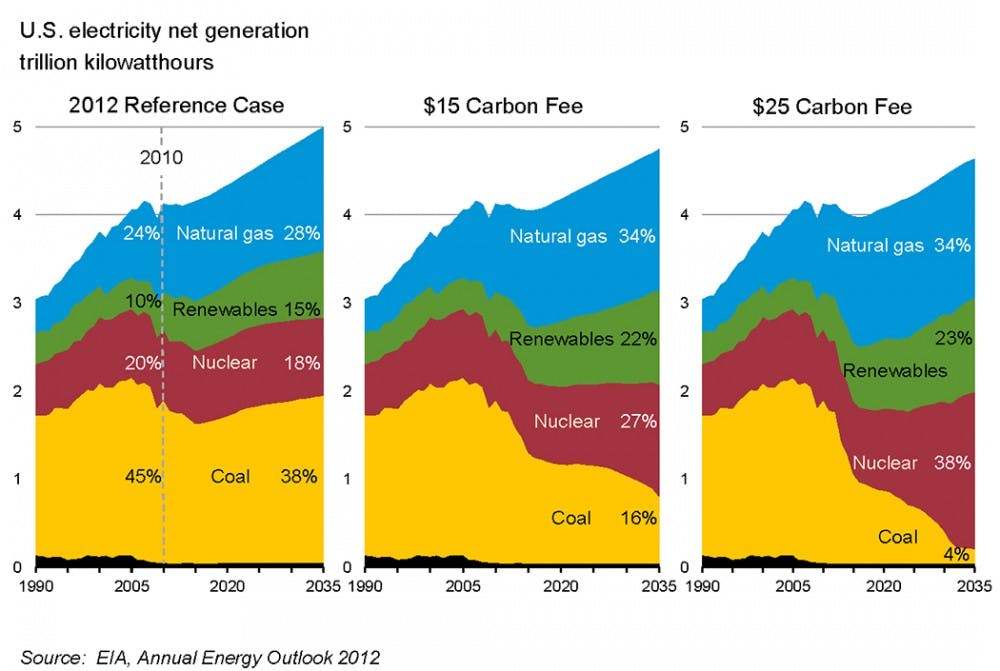

“[A carbon tax] makes the relative cost of carbon-emitting energy higher and the renewables comparatively [cheaper], so it should really accelerate the transition to renewable energy,” Phillips said.

This could lead to growth of the green energy while reducing U.S. dependence on unreliable sources of energy.

“A carbon tax would also make our economy more resilient, because it incentivizes us to move towards a decentralized, renewables-based non-fossil fuel economy and that’s more resilient in general, than one that relies on pulling [oil] out of the ground from countries in the Middle East,” Wolz said.

Despite the advantages of a carbon tax, certain drawbacks merit examination. For example, a carbon tax is most effective if implemented globally.

“[Climate change] is a global phenomenon that demands a global solution. You would want carbon tax to cover everything — all emissions from wherever they are,” Phillips said.

Without a carbon tax implemented internationally, there is a greater risk of carbon leakage and production outsourcing to countries with fewer barriers on emission production, causing the same amount of carbon pollution produced, just elsewhere in the world.

With respect to the University, students may see an increase in transportation costs.

“People who drive a lot, people who fly a lot, they would be paying more, but I wouldn’t say that is paying more unfairly because we are currently paying an artificially low price — is what I would argue. We have so many fossil fuel subsidies in the U.S. ... We’re just paying the bare bones, what it costs to get [the oil] out of the ground. We’re not paying for the damage that we’re causing,” Wolz said.

Additionally, movement away from fossil fuels could encourage the University to move towards more sustainable forms of energy.

“Dominion — our power provider — they would have a much stronger incentive to start producing renewable energy which is getting cheaper by the day, so the net result may be that we have cleaner energy and that it could be cheaper,” Wolz said.

However, before the implementation of a carbon tax, certain changes would be necessary.

“First of all, the administration would have to actually accept that climate change is real and that humans are responsible for it and therefore changing the behavior of humans, through a tax or some other way, is part of the solution,” Phillips said.