Assoc. Prof. Claudrena Harold said the University’s Black Student Alliance is “without question” the most important organization on Grounds.

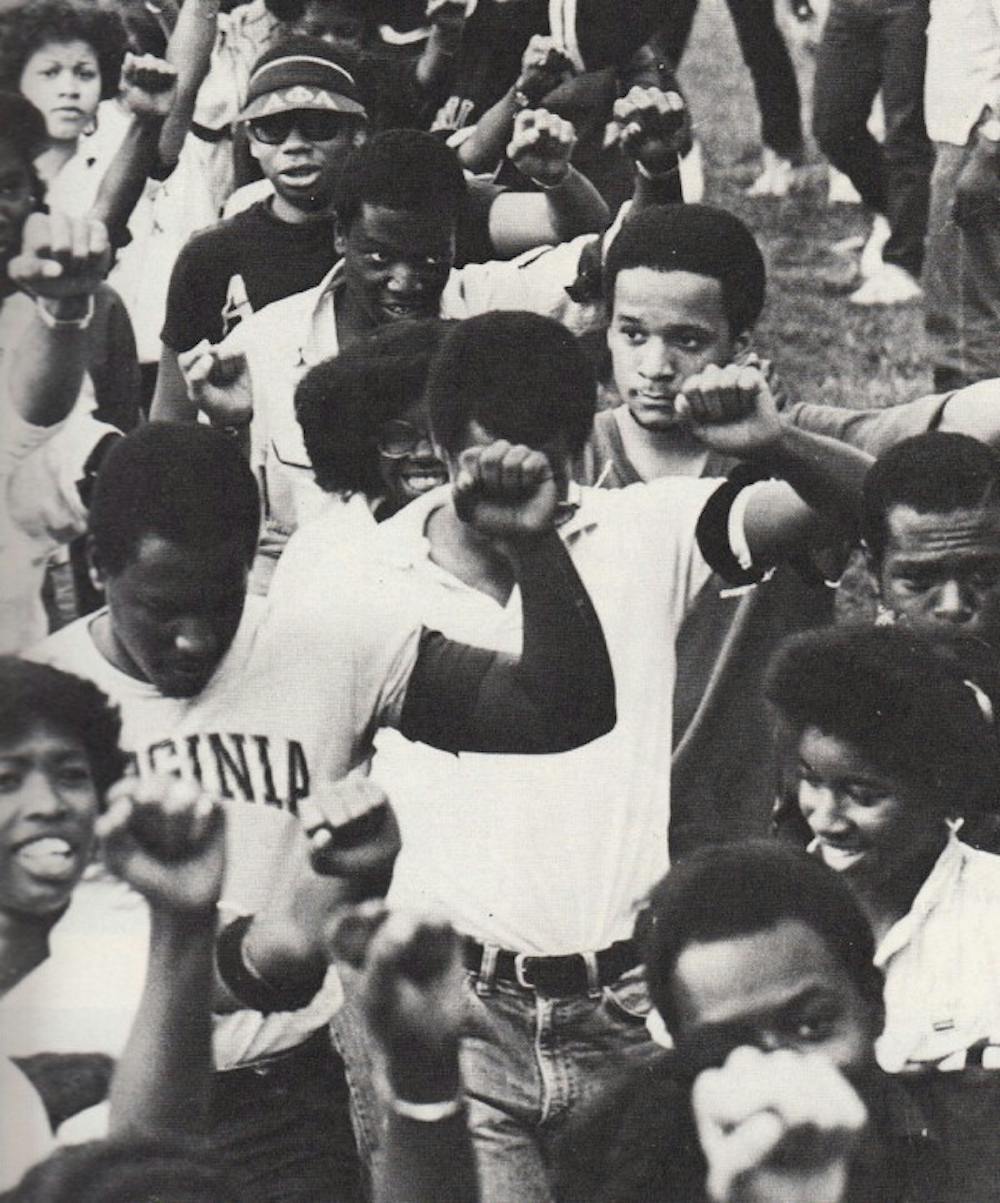

The University’s history with racial integration and equality has been a complex one — one that the Black Student Alliance has been at the forefront of since its inception in the 1968-69 academic year.

The first black students at the University

The first black student to attend the University was Gregory H. Swanson, who was admitted to the Law School in 1950 only after he filed a legal suit to gain entry.

The Board of Visitors originally rejected Swanson’s application on the basis that “the Constitution and the laws of the State of Virginia provide that white and colored shall not be taught in the same schools,” according to their written response.

Despite eventually being granted entry into the Law School, the twenty-five year old did not graduate due to the racial hostility and isolation he experienced while on Grounds. The University’s first black graduate was Walter N. Ridley, who was accepted in 1951 and received his degree in 1953.

The BSA was created more than a decade later to represent the growing population of black students on Grounds. Originally known as the Black Students for Freedom, the BSF was a student initiative which has had a variety of goals related to both the University community and the broader Charlottesville community.

“There can be no understanding of the integration of African-Americans into this University without looking at the Black Students for Freedom and the BSA,” Harold said. “They are central to the story of racial transformation at U.Va.”

BSA’s beginnings

College graduate John Charles Thomas was one of the first presidents of the BSA during his undergraduate years from 1968 to 1972, and was actively involved in instituting some of the original programs of the BSA.

“We looked at ourselves as a voice that needed to be asserted at U.Va.,” Thomas said. “So we were always at the forefront at arguing for black courses, black professors and more black students. We were pushing for integrating U.Va.”

Though Thomas said he remembers having a positive relationship with many faculty members and the administration — who he recalls as being receptive to many of the broad goals of the BSA — the University was not always as progressive as it hoped to be.

A University-wide referendum in the early 1970s indicated most students would endorse, or go on strike for, increasing the percentage of black students to 20 percent, but in 1969 the University was only 1.3 percent black.

“I can remember basically demanding that U.Va. change,” Thomas said.

The BSA worked actively to recruit more black students and professors, institute an African-American studies program and also address particular issues around Grounds.

When the Cavaliers scored a touchdown during football games, students would first sing the Southern song “Dixie” before the “The Good Ol’ Song” and a man mounted on a horse would carry a Confederate flag around the stadium.

Thomas said he and BSA members were vocal in adamantly protesting the use of the Confederate flag, which they argued has an irrevocable tie to slavery and racial segregation. By the time Thomas graduated in 1972, he said this particular tradition was obsolete.

The BSA was also active in traveling to local and Virginia high schools to encourage young black high school students to apply to and attend the University.

Thomas said he was formally hired by the administration to visit schools — where he would meet with guidance counselors and speak at assemblies in an effort to recruit future black students.

“U.Va. was very well educated and very international. We had scholars from all over the world,” Thomas said. “These people in Charlottesville — they were interested in changing the world and I was just one of the young kids who they happened to come upon in that moment who might play a role in that.”

Great leaders become great figures

After graduating from the College in 1972, Thomas attended the University’s Law School. Upon earning his J.D., Thomas practiced law with a private firm for several years before being appointed to the Virginia Supreme Court.

Thomas was the first African-American justice to sit on Virginia’s highest court and also the youngest. His portrait currently hangs in the atrium of the Law School.

But Thomas is only one of the BSA’s distinguished and esteemed alumni — a fact which Harold has emphasized as one of the greatest legacies of the BSA.

“Like any organization the Black Student Alliance has experienced its share of changes [and] transformations,” Harold said. “It has at times been reflective of the times and it is at times transcended the times. It has pushed the University, but it has also been a critical training ground for African-American leaders who have gone on to do some amazing things.”

Like Thomas, Leroy R. Hassell, a 1977 College graduate and BSA member, became a justice on the Virginia Supreme Court. Hassell was the court’s first black Chief Justice, serving two terms from 2003 to 2011.

Deborah Saunders-White, who was the president of the BSA in the 1970s, became the first female Chancellor at North Carolina Central University, a historically black college, in 2013.

“The thing about the history of BSA is I am always finding these figures of import,” Harold said.

Current BSA President Bryanna Miller, a fourth-year College student, said she feels some of the most exciting events are ones that engage underclassmen to build leadership skills.

For example, the BSA recently hosted its second Black Leadership Academy — a four-day-long retreat targeted at underclassmen to participate in student run workshops. Future programs are then designed by those attendees of the academy, like the Black Man Brunch or charity functions for the homeless.

“Those are the most exciting because it’s coming from the next generation of students that are going to lead at the University,” Miller said.

The BSA today

According to 2016 figures, the University’s undergraduate student body is 6.4 percent black, which equals a little more than 1,000 students. Every black student at the University is a member of the BSA, although regular attendance to meetings and events varies, Miller said.

The BSA has several subcommittees focused on topics like academic and career development, leadership development and political action. The organization has dozens of events on Grounds each academic year — ranging from small study groups to leadership programs to the Black Ball, which boasts more than 400 attendees.

One particular annual event, Black Culture Week, has been put on annually by the BSA since 1970. It celebrated its 45th anniversary in 2015.

The BSA has also participated in several major protests in recent months — another legacy of the organization which remains strong both here on Grounds and in the greater Charlottesville community.

From Thomas’s protest of the use of the Confederate flag during his time at the University to current initiatives, the BSA has always had an active voice in shaping the social climate on Grounds.

In the 1970s, the BSA was a key student organization protesting for divestment of the University from its stockholdings in South Africa during apartheid and advocating in support of affirmative action. The BSA has also episodically been involved in protesting for a higher living wage for workers at the University for decades as well as against instances of police brutality against blacks.

In response to the violent arrest of then-third-year College student Martese Johnson in March 2015, Black Dot — with the support of the BSA — rallied hundreds of students, faculty and community members in protest of the discord between law enforcement and black people in both locally and nationally.

In September 2016, the BSA staged a die-in outside of Old Cabell Hall to protest police brutality and show support for the national Black Lives Matter movement.

The BSA also frequently co-sponsors events with other organizations and engages with other student voices to combat specific social or political concerns.

Overall, Miller said she thinks black students need to be engaged and actively supported here by not only other students, but faculty and administration as well.

“Black students need to be reassured that they matter and that their issues matter,” Miller said. “Their issues are being valued, their accomplishments are being valued.”

The BSA for decades now has been a central part of connecting and engaging students. The BSA is the anchor of black U.Va. and the wider University community, Harold said.

“That an organization can celebrate 48 years of history and can say that there has never been a year or there has been an extended period where they have not been in existence — is remarkable,” Harold added.