Television shows have never been good with texting. It’s the 21st century — any attempt to depict real life is woefully inadequate without also depicting phones and their centrality in modern communication. Yet despite this necessity, even the most skilled directors have long struggled to produce anything resembling real texting on television.

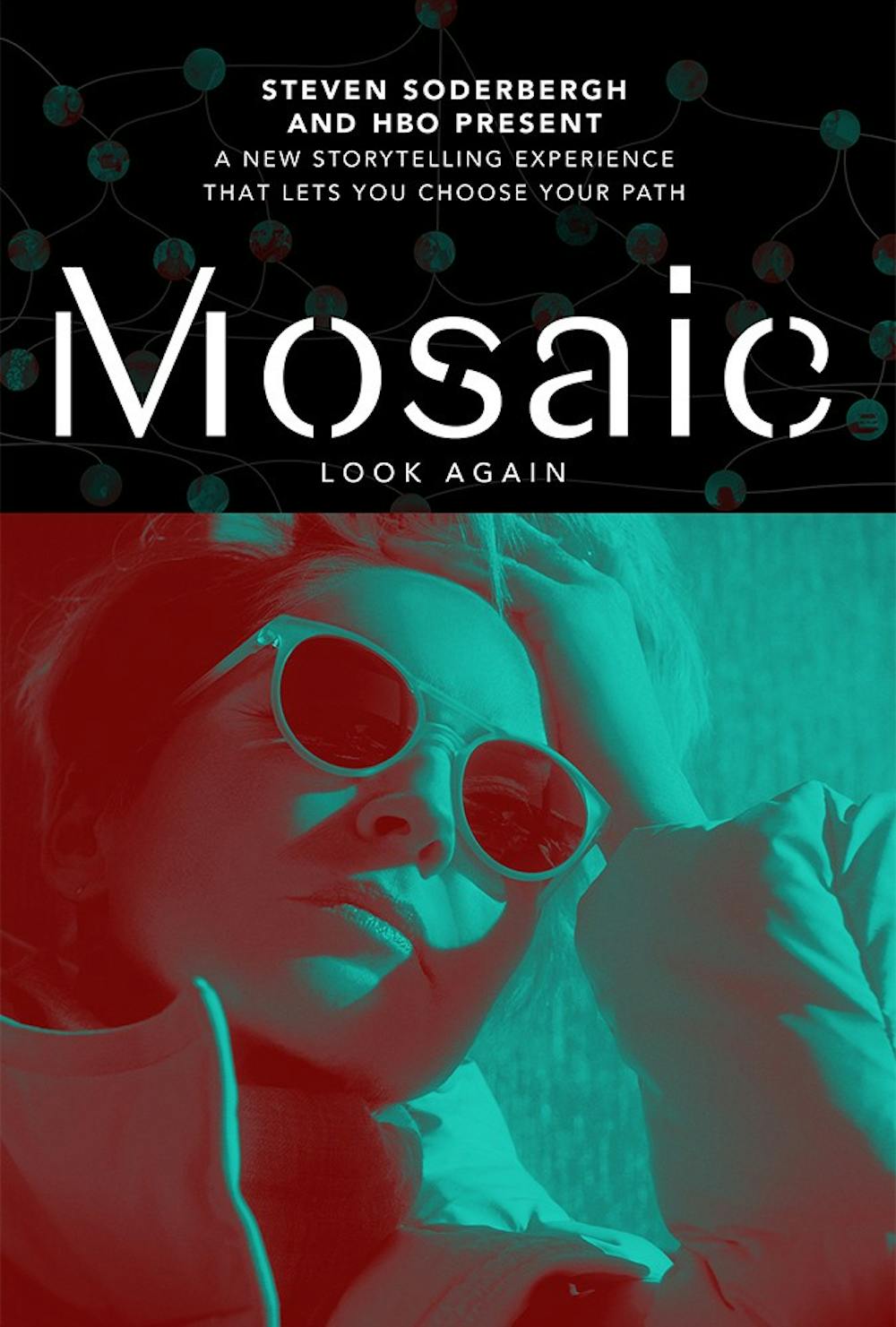

Steven Soderbergh’s HBO miniseries “Mosaic,” released over the course of past few weeks, provides an exceptionally elegant solution. “Mosaic" is notable for its creative use of technology in general — it garnered attention for releasing a choose-your-own-adventure style application to accompany the traditional viewing experience — but the show particularly excels at solving the historically tricky problem of depicting on-screen text messages. It’s worth taking a look at what “Mosaic” does that works so well.

BBC’s popular series “Sherlock” was one of the earliest prestige television shows to make a serious foray into on-screen texting. “Sherlock” is meticulously crafted and creatively executed from a filmmaking perspective, and it’s notable for its creative use of technology and text. Even so, the show never managed to create text messages that felt natural on the screen.

Late in the show’s first episode, Dr. Watson (Martin Freeman) receives a message from his enigmatic friend Sherlock Holmes (Benedict Cumberbatch). As Watson pulls his phone out of his pocket, the message appears on the screen in clean, simple, white typeface. The message reads, “If inconvenient, come anyway. SH.”

There’s something undoubtedly off about the way this message appears. Sherlock does a better job handling the text message than some other shows — Sherlock never actually shows the phone screen on camera, like some shows do — but their solution is far from perfect, and the problems, though subtle, have unfortunate consequences for the success of the scene. In this case, the incongruities in the on-screen message undermine the delicate and complex characterizations of Sherlock and Watson. The greatest detective in the world doesn’t know that signing his initials in a text message is redundant? Most grandmothers don’t even do that anymore.

Or, even worse — Watson and Sherlock don’t have each others’ numbers saved in their phones? They’re roommates, and the first thing roommates do is exchange numbers. Why is “it’s” excluded from the sentence? No one types out the whole word “inconvenient” but doesn’t bother to put the “it’s.” That syntax is a lazy caricature of digital communication. The incorrect grammar makes the message read like an old-school telegraph — not a text message. The bad texting shatters the viewer’s perception of the characters. Modern audiences are so intensely familiar with the details of digital communication that anything less than perfect is noticeable instantly.

“Mosaic” provides a much more elegant solution. One of the show’s very first scenes features a text conversation between wealthy writer Olivia Lake (Sharon Stone) and her assistant JC Schiffer (Paul Reubens). Comparing the texting scenes in “Mosaic” with “Sherlock” underscores how important details are.

In “Mosaic,” messages appear on the screen letter by letter in a clean, bold, white type.

The font is distinctly different from any font that actually appears in a messaging app, which counterintuitively serves to make the messages more realistic. Sherlock’s Helvetica is similar enough to what phones actually use that its slight non-reality is emphasized. The boldface that “Mosaic” uses avoids entering this “uncanny valley” of text message lettering.

When texts are sent in “Mosaic,” the sound isn’t a random series of beeps like in Sherlock. The texts in “Mosaic” are accompanied by the instantly recognizable iPhone messaging swoosh. Olivia Lake is a glamorous socialite. She often wears a white fur coat. She lives in Summit, Utah. Of course, she has an iPhone. Anything else would be unrealistic. If her texts were accompanied by any other sound, the viewer would instantly feel that something was wrong.

Additionally, the syntax of the messages is spot-on. Olivia uses no periods, but she does use question marks. She spells words fully. The first letter of the message is capitalized and the apostrophe is included in “wasn’t.” Olivia is typing on an iPhone, and that’s how iPhone messages look. When Soderbergh needs to clarify which character is sending a message, the name is noted before the message appears, rather than having the character sign the name within the message itself. This avoids the problem presented by Sherlock’s cutesy little “SH” signature. The name isn’t noted in front of every message — only when it’s absolutely necessary.

These differences may seem subtle, but they matter for the viewer’s experience. Texting is such a central part of modern communication that on-screen text messaging has become just as important as spoken dialogue. When it’s wrong, the effect is equally jarring. Olivia wouldn’t say “y’all,” and she wouldn’t type “ttyl.” “Mosaic” deserves praise for its attention to detail. The show provides a commendable solution to a problem that has proven vexing for even the most accomplished directors.