Every day for eight weeks I entered the Virginia Museum of History and Culture through a hidden side door. I weaved through a dim hallway past unused furniture and exposed pipes until I reached the elevator. My floor was 2, but only in the abstract, because my office had no windows. Each day I was greeted by the drab accoutrements of office life — sticky notes, paper clips, a gray Formica desk, the Windows start-up sound.

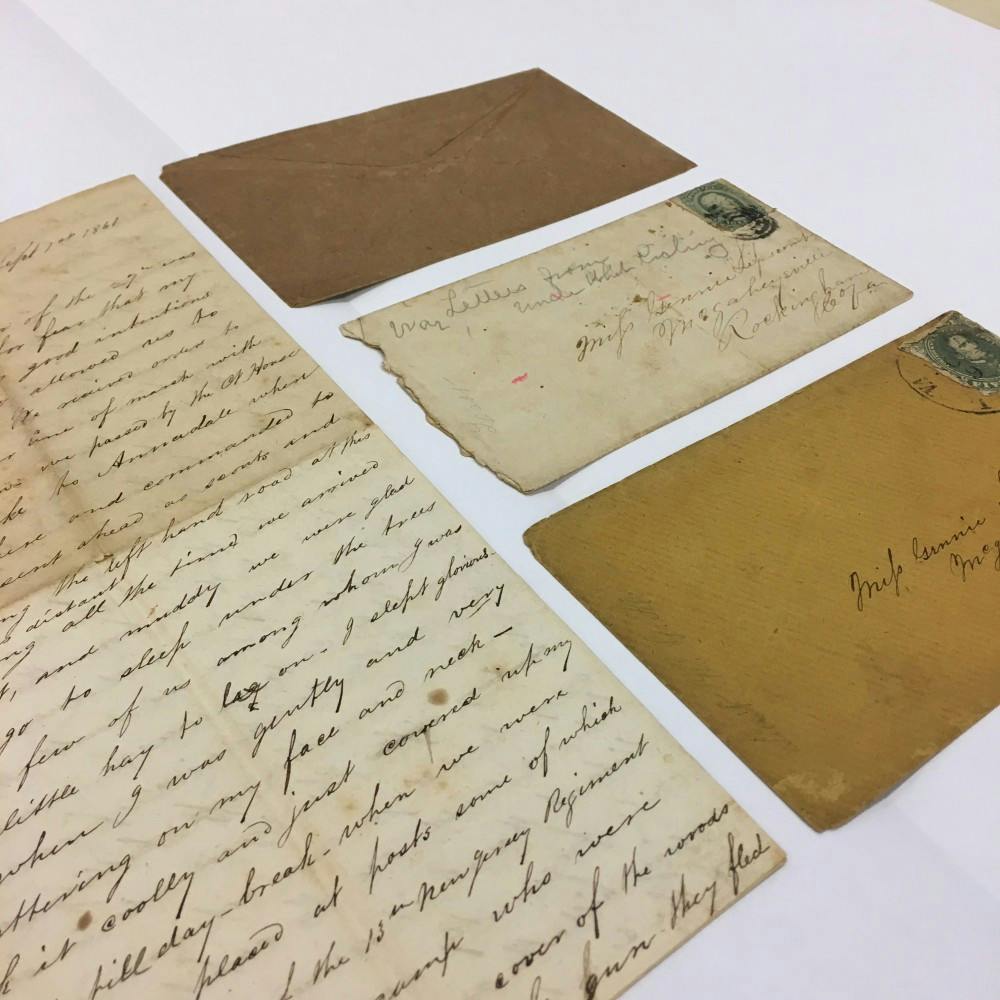

I spent the summer reading and organizing correspondence from Civil War soldiers. On my desk at the VMHC sat eight large boxes groaning with letters inherited from a defunct archive. The yellowed documents had been stuffed willy-nilly into folders. Even preserved as they were, the years had not always been kind to the pages, and the yellowed, beaten, tattered, faded letters were often difficult to read. My job was reorganizing the artifacts according to the system of the VMHC.

The job sounds boring, but it isn’t. How can I explain the allure of a summer spent digging through this interminable stack of old papers?

The letters, of course, were handwritten. Handwriting is rare in modern life. When we do write by hand — lecture notes, comments from professors — the words have a way of going unread. But down in the archives, handwriting takes center stage. Swooping ‘f’s and long, jaunty ‘y’s betray clean hands and a posh accent, perhaps a father in the Senate. Shaky letters and shaky spelling reveal calloused hands, hardened from decades of farming.

It’s easy to see when a semi-literate soldier dictated a letter to a more erudite friend, because the handwriting improves. Occasionally letters from even the best writers come out as little more than a penciled scrawl. Perhaps the paper was balanced on a knee, or pressed against a tree trunk — the raw conditions of camp or the panic of impending battle become visible as ‘e’s and ‘o’s become indistinguishable.

The soldiers rarely wrote about battles or politics. They wrote about shoes and the dramatic lack of decent ones. They wrote about their dreams, often sweet distractions from the hardships of service. They wrote about how the girls from their own state were prettier than the girls from other states. They wrote about turning 19 all alone, hundreds of miles from home. They wrote love poems to their wives and girlfriends. They complained about the unreliable postal service.

In the hundreds of letters I read, no subject appeared more than food. Military rations were unpleasant and inadequate, and war drove the price of other foodstuffs to sky-high prices. Soldiers complained incessantly about spending gigantic chunks of their wage on small pieces of meat. They asked their families to send care packages with their favorite treats — apple butter, peaches, bacon and of course whiskey. Many of the soldiers had to cook for themselves for the first time, and the letters occasionally included humorous, self-effacing descriptions of the men attempting to spruce up their meager rations. One Jewish soldier remarked that it would be easy to keep Passover, because the only food they ate was hardtack.

I had to create a small genealogical note to accompany each collection of letters. My tools: a haphazard collection of census records, enlistment records, obituaries and online gravestone databases.

19th-century naming customs complicated my job further. There were two Thomas Millers in the 9th Virginia Infantry. Which was married to Catherine Miller? She is buried in Rockingham County, but both Thomas Millers are buried in Culpeper. The rolls of the 9th Virginia say Thomas Miller was killed in 1862, but I am holding in my hand a letter from Thomas Miller, dated 1864. Did he lie about his age when he enlisted? Did he marry his first cousin, or was there more than one Catherine Miller in Rockingham? Are Catherine Virginia Miller and Virginia Catherine Miller the same person? Are they even related?

Yet with some elbow grease, the pieces almost always fell into place. A census record led to a gravestone which led to a cemetery where much of the family is buried, and there a gravestone revealed that Private Thomas Miller was born in 1837 and died at Second Bull Run.

This summer, my job was to tease as much information as possible out of scant resources — the crossing of a T, the price of pork, the weatherbeaten inscription of a gravestone. Archival work doesn’t seem sexy, but it shares its core ethos with more glamorous professions. This summer, I was a paleontologist, thrilled to find that the rock they’re dusting off is a dinosaur claw. I was a detective, often literally searching to find where the bodies are buried.

“Look what I discovered in the archives!” historians and students often say. This refrain is just a tad disingenuous, I believe. In a functioning archive, every document has been seen before. Every scrap of paper has been conscientiously, meticulously arranged to make discovery as easy as possible. But it’s a testament to the delight of archival discovery that even secondary finding can be so exciting for researchers and writers. This summer I had a chance to take the first crack at unearthing these documents. Archival work is about focus, detail and pulling meaning from the ether of history. What’s boring about that?