Throughout the summer, Charlottesville community members and students took to the streets alongside 26 million Americans to protest police brutality and systemic racism in America. Since then, the nation witnessed record-breaking voter turnout in the 2020 elections, the restriction of chokeholds in 62 percent of the country’s biggest police departments and resistance among government leaders to implement major reforms.

In addition, various other art forms were created to honor the victims of police brutality and advocate for change. The Black Lives Matter movement put a spotlight on the lack of diversity and representation in the media and art world. Local artists are combating this absence by documenting their experience as Black artists through their creations.

Documenting summer 2020

Eze Amos, a Charlottesville photojournalist, used his Instagram to showcase his walks during Black Lives Matter protests in summer 2020, documenting protestors in action in Charlottesville and Richmond.

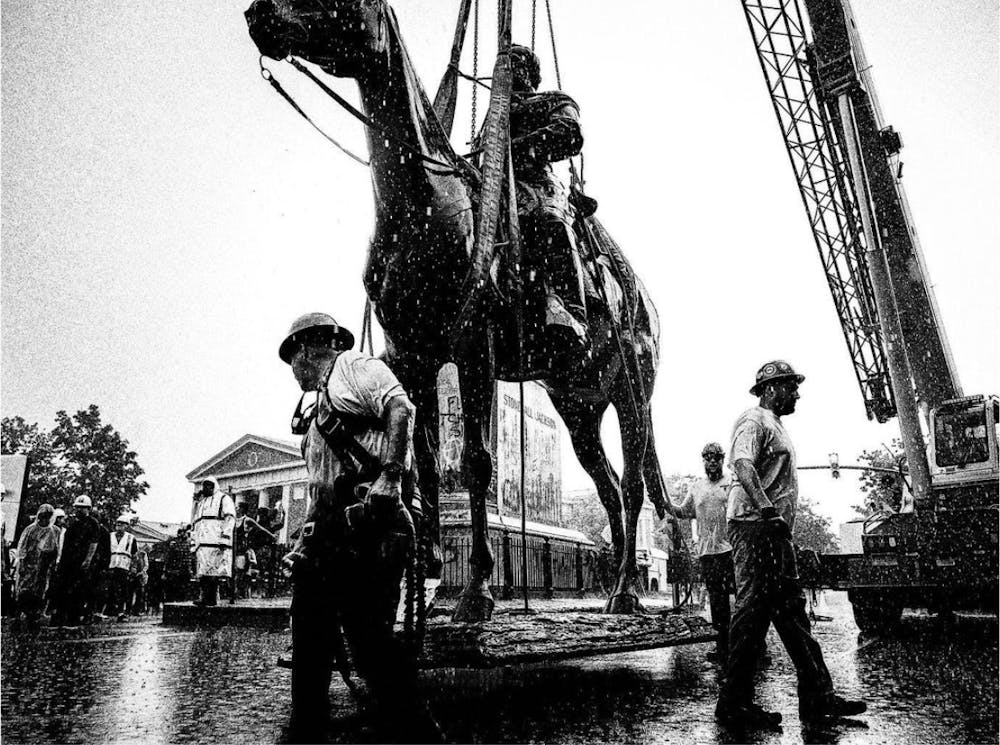

Courtesy Eze Amos

“This revolution will be photographed,” Amos wrote in the caption of an Instagram post.

Amos was one of the many Black photojournalists who used their skills to document the Black Lives Matter protests. Photojournalists stood on the front lines alongside protestors and captured the spectrum of emotions sparked by protests, using their social media platforms to share moments that were not broadcast on national news.

“Folks go out in the street to protest, they write signs, they have sit-ins, they have public disobedience — whatever form of protest they adopt, our job as artists is to help them amplify whatever message they are trying to push,” Amos said.

The infamous Stonewall Jackson statue on Monument Avenue in Richmond — a grassy mall which is home to numerous Confederate statues — was removed by cranes on July 1. As the statue was removed from its pedestal, hundreds of protesters cheered in the pouring rain — Amos was there to document that historic moment. When he drove back to his home in Charlottesville, he recounted his experience witnessing history to The Cavalier Daily.

“It's a movement that is finally getting people to pay attention and listen to what folks have been saying for all these years about police brutality, ... the injustice of how they treat black people, implicit bias, all those things that everybody has been talking about Trump for as long as we can remember,” Amos said.

Amos stated he believed in order to create lasting change, artists must keep pushing the stories and communicating the messages of protesters that mainstream media doesn’t cover.

Courtesy Eze Amos

Addressing the lack of representation

“It's very important to promote creators from all walks of life,” Amos said. “[When I got to Charlottesville], it took me forever to break into the market and get people to pay attention … Black photographers and Black artists are never given the opportunity to prove themselves because, somehow, there’s just an assumption that we’re not up to par.”

The increase in exposure Amos received due to his documentation of mass protests gave him the opportunity to share his photos with reputable news organizations like the New York Times. On June 21, Instagram featured Amos in their “WHAT NOW, TAKE ACTION” campaign. However, despite Amos’ recent access to a larger platform, Black representation in art and media has historically been low.

In 2019, art historians, statisticians, professors and art curators surveyed art collections of the 18 major museums in the United States. The researchers set out to find the gender, ethnic and racial composition of artists represented in these collections. The results revealed that 85.4 percent of pieces in the collections were created by white artists and Black artists’ work made up 1.2 percent of the art in all major U.S museums. This is despite Black Americans composing 13.4 percent of the U.S. population.

This disparity isn’t just present when it comes to visual art. In the film industry, researchers at the University of Southern California analyzed the top-grossing 100 films of 2015, and their study revealed that only four of the 107 directors were Black or African American and only nine of the movies had a Black lead or co-lead. #OscarsSoWhite began trending in 2016 on Twitter in response to the award show’s lack of minority representation in their nominations.

However, even when Black Americans are represented in media though, their portrayals are often inaccurate and stereotypical. In a literature review on the impact of media representations on the lives of Black men and boys, researchers at The Opportunity Agenda, a social justice communication lab, found that Black males are stereotyped and underrepresented in media. The report’s findings indicated that negative associations such as criminality, unemployment and poverty are exaggerated while positive associations are limited to physical achievement and musicality. These stereotypes create erroneous portrayals of Black males. The researchers concluded that producers of media must create more accurate portrayals of Black men in the media by incorporating more African Americans in production.

Charlottesville-based photographer Jason Lappa thinks that the BLM movement is broadcasting the unheard stories of minorities to the world, including those of Black artists and creatives.

“What is revolutionary are the eyes and voices behind the photographs we are starting to see in the major media outlets,” Lappa said in an email to The Cavalier Daily. “The eyes of Black and brown photographers such as Ruddy Roye, Sheila Pree Bright, Vanessa Charlot, Courtney Coles, Julio Cortez, Andre Chung and Kris Grave, The stories of Black people told by Black people — that is the revolutionary realization that is just now beginning to take hold in the mainstream.”

Amos believes that art has the power to recondition society's perceptions of Black Americans and their stories.

“[It’s like how we are all] conditioned in a dark alley to picture a shadow of a big person coming towards you [and] nine out of ten times you are picturing a black person,” Amos said. “It's something we’ve just been conditioned to think overtime from the movies and all of the books and it's wrong. We as artists can rewrite our stories and tell them in a better way.”

The push to promote Black representation and diversity extended into the business world as well. Black community members and allies participated in an economic boycott on July 7 in what was known as Blackout Day. Participants were told not to spend a dollar at stores, restaurants or businesses unless they were Black-owned in an effort to highlight the 1.3 trillion dollars in buying power that Black Americans have in the U.S. economy.

On last year's anniversary of the emancipation of enslaved laborers in the United States, also known as Juneteenth, Beyoncé released her single “Black Parade” with the proceeds from her single going to support the singer's Black Business Impact Fund. The fund awards $10,000 grants to small Black-owned businesses. The song was released along with a directory of over 700 nationwide Black-owned businesses. One business featured was the African inspired art store UzoArt, a business owned by Uzo Njoku, artist and Class of 2019 alumna.

“It was crazy — I was like, Beyoncé!” Njoku said, laughing while reminiscing about the moment she found out she was featured in the campaign.

Njoku was overjoyed to be included among the likes of other talented Black artists and creators. Even though she expressed that more celebrities should follow suit, Njoku emphasized that strictly supporting Black business owners is not as simple as it may seem.

“We all say we should support Black businesses, but a lot of these processes, payment and shipping processes are giving money to a white man,” she said. “However, I still think support is important for Black business owners.”

Njoku’s business saw an increase in sales as a result of the support redirected to Black-owned businesses. Njoku, in turn, donated extra funds towards organizations involved with the Black Lives Matter movement and fellow artists struggling due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Rewriting the narrative

Njoku’s art business took off with the creation of her coloring book, “The Bluestocking Society,” which was released in August 2018. Unlike most coloring books, Njoku featured powerful women of color from diverse cultures. Since the release, she has amassed 39,000 followers on Instagram, and her business UzoArt expanded to include art prints, phone cases, puzzles and more. Njoku’s unique artistic style consists of powerful portrayals of African women with striking colors and bold West African patterns.

“I paint mostly Black women because it is who I am,” Njoku said. “If you look back in art history, famous paintings have always been from the gaze of a man. In the past, the way they were posed was very minute. Fast forward to now, women in the media are portrayed in a very vulgar sense and we’re hypersexualized.”

It is Njoku’s belief that it is important for women and, in particular, Black women to reclaim their stories through art. In her painting entitled “Working Woman,” Njoku depicts a Black woman smoking at the end of a workday. Njoku put a spotlight on the stressors that Black women face in everyday life. The painting is captioned, “Roll another one. You’ve earned it, even if you haven’t. Stepping out in Ankara is enough. Wrapping your hair is enough. This work bleeds beyond the boardroom — roll as many as you please.” The caption points to the multiple layers of oppression Black women endure in and outside the workplace, and the impact it has on wellbeing.

This concept of intersectionality was developed by Kimberle Crenshaw, a Black civil rights advocate and lawyer. She defines the theoretical framework as the overlapping of social problems such as racism and sexism that incites further discrimation. Crenshaw explained that the failure to address disadvantages for every member of a particular group leads to exclusionary solutions.

Researchers found that Black women endure a heightened experience of emotional taxation from peers in the workplace. In the study, Black women reported experiencing anxiety around certain white co-workers and felt that they must always be prepared to deal with potential discrimination. This additional emotional burden is associated with detrimental effects on their health and well-being, which threatens their ability to do well in the workplace.

Njoku’s art highlighted the power Black women express in the face of adversity.

“I put the woman I draw in very powerful poses and gazes,” Njoku said. “Even if they are naked, they are naked in a powerful way.”

One of Njoku’s portraits was of Oluwatoyin Salau. Salau was a 19-year-old Black woman and community organizer who was sexually assaulted and murdered in June 2020. Njoku gave out 100 free prints of the late Salau on her Instagram, captioning the photo, “Rest in Paradise Toyin. How many more lives will be lost?”

Salau’s death sparked a national outcry and intensified the #SayHerName movement, which aims to “bring awareness to the often invisible names and stories of Black women and girls who have been victimized by racist police violence.” It was created in December 2014 by the African American Policy Forum and Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies.

#SayHerName increased in use after the March 2020 death of Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old Black woman who was shot by police while sleeping in her home in Louisville, Ky. In September, Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron ruled that no officers would be directly charged in relation to Taylor’s death — a decision which resulted in a national outcry on social media. The two officers were fired in early January.

Some now argue that Taylor’s death has become commodified and turned into a gimmick, pointing to the mass production of T-shirts sold with her image alongside the phrase “Arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor” and posts on social media that said, “Today is a good day to arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor.”

Teen Vogue op-ed writer Precious Fonderson argues that the #SayHisName and #SayTheirNames hashtags used in response to the death of George Floyd are in fact co-opting the original phrase aimed to focus on the overlooked deaths of Black women. She explains that Black women do not receive the same level of support from BLM advocates as Black men.

Sahara Clemons, a Charlottesville artist, is also reclaiming the oppressive narratives Black women face. Earlier in 2020, Clemons was invited to create a community mural by the Charlottesville Mural Project. Her mural — entitled “Say Her Name” and located near 10th Street — depicts a Black woman lying in a bed of clouds holding a lightning bolt.

Clemson’s mural was inspired by her mother, who is actively involved in the Charlottesville community as the director of programs for the Charlottesville Area Community Foundation.

Courtesy Denise Brookman-Amissah

Clemons’ artwork showcases her love for textile, design and bold colors,and her inspirations resulted in a mural that brings Black women to the forefront.

“[Black women] are minorities but also have invisibility within the minority community,” Clemons said. “Taking strides to have our voices known is what I really wanted to project when I was designing the mural.”

Clemons hopes that the Black women of Charlottesville can be able to see themselves in her artwork. The mural is located in Vinegar Hill, a historically Black neighborhood that bulldozed in the name of an urban renewal project in the 1960s and has since been gentrified. Clemons viewed her work as an intersection for the different communities of Charlottesville.

Clemons’ invitation was a part of the Charlottesville Mural Project’s efforts to showcase the art of diverse artists in the Charlottesville community through public art projects. In addition to a mural by Clemons Library, the project included art pieces entitled “This is What Community Looks Like” by photographers Lisa Draine, Ézé Amos and Kristen Finn and “Together We Grow” by Jake Van Yahres and Christy Baker in the Downtown Mall.

The power of art as activism

Clemons loves that art allows her to express the pain, frustrations and beauties she has experienced as a Black person in America — feelings that cannot always be easily expressed verbally. Clemons said that using art as activism is a way of showing one’s emotions to the outside world — its visual bold statements hold the power to be an effective method of peaceful protest.

Art by Clemons has been featured in Vinegar Hill Magazine, a Central Virginia publication striving to promote inclusivity, entrepreneurship, art and politics. Her work appears in articles about the long-term and short-term effects of COVID-19 on the Black community in Charlottesville. Her painting, “Tired of Healing My Wounds,” depicts a Black woman in agony leaning against an eviction notice on her front door. Another painting, “Feed,” portrays Black children at the lunch table with food trays while across the table, two more children sit with their trays replaced by a damaged vehicle, medicine and housing costs. Through her work, Clemons confronts the challenges of food security, affordable housing and health issues Black community members face in Charlottesville.

“The series helped me confront a lot of the things that are happening right now and put it into a piece,” Clemons said. “In terms of how [COVID-19] and the Black Lives Matter movement are escalating at the same time, how we are trying to combat a harsh disease and a harsh world.”

To facilitate change, artists supported the BLM movement by using their respective talents to produce songs, documentary videos and artwork to empower the movement and educate the public about the history of injustice towards Black people in America.

“The role of documentary photography in the BLM movement is unquestionably invaluable,” Lappa said. “Those who are willing to bear witness to the truth to create a visual record of historical events are indispensable where the education of future generations are concerned. Creative projects like OneForGeorge contribute to a sort of hive mind that drives a collective understanding of what the BLM movement is actually about.”

In June 2020, Lappa was involved in a creative project entitled “One for George.” The three-part creative project consisted of a portrait series, hip-hop song and accompanying music video.

It was organized and directed by Damani Harrison, a Charlottesville musician and activist, and Eric Hurt, a director and cinematographer. Lappa took photo portraits of the creators’ friends and family in the Charlottesville area. The three artists created a series that embraced the city’s diversity and highlighted the unification of Charlottesville in support of its Black community.

Courtesy Jason Lappa

“Art is not just an expression — it can be revolutionary,” Hurt said. “You can reach people more easily than just telling them what's bad and in some ways, you can reach them easier than if they were to watch the news or a documentary. [The news] is real life, but … the emotions aren’t involved there.”

Hurt has known Harrison for around a decade, and the two worked with each other on multiple projects before. After the death of George Floyd, Harrison emailed Hurt about the song Harrison made. The very next day, the two began working on the “One for George” project. The purpose of their project was to artistically communicate Damani’s lyrics in an emotional and inspiring approach.

“Generally, art and imagination tend to come before the execution of things,” Hurt said. “It bolsters the vision but also bolsters the emotion of people.”

According to Hurt, the style of the music video he and Harrison created is reminiscent of Jay-Z’s “99 Problems” video. At the start of the video, Harrison emerges from the darkness delivering his first lines.

“Woke up this morning to a post / Another black soul getting choked,” Harrison rapped.

The lyrics were accompanied by video clips of police brutality, lynchings and hate crimes against Black Americans throughout history. The imagery also wove in references to the 1969 Stonewall riots by LGBTQ+ people, the massacre of the Lakota people at Wounded Knee and other historic instances of oppression perpetrated by white America. According to Harrison, the heavy tone of the music video illustrates the raw truths of life as a minority in America.

“There is a history of it, not just police brutality today,” Hurt said.

Hurt explained that the black and white picture of the music video is analogous to racial tensions in the country. Hurt and Harrison believed it was important to incorporate the struggles other groups face, including the LGBTQ+ community. In one scene, the black and white theme is contrasted with a rainbow Pride bandana worn by Harrison’s transgender son. The imagery highlighted how Black transgender people face some of the highest levels of discrimination compared to transgender people with other racial and ethnic backgrounds. They also experience unemployment and homelessness at higher rates.

Hurt believed that, in order to sustain momentum in the Black Lives Matter movement, artists should continue to amplify the voices of Black Lives Matter activists. On the evening of July 22, 2020, music played along Monument Avenue in Richmond, Va. Two dozen musicians performed “Somewhere over the Rainbow” and “We Shall Overcome” at the base of the Robert E. Lee monument. The monument had become the center of the BLM protests and was unofficially renamed by protesters as Marcus Davis Peters Circle after a Richmond Black man who lost his life as a result of police brutality. The vigil was held in honor of Elijah McClain, a 23-year-old Black man and violinist who died after being choked by Aurora, Colo. police.

The monument area was covered in phrases such as “Black Lives Matter” and “We won't stop” as it became a stage for Black Lives Matter activists to spread their messages. On the night of July 28, 2020, The George Floyd Foundation unveiled a hologram in Floyd’s honor at the statue. The event featured Black musicians and artists from Richmond before the hologram lit the sky with Floyd’s face and the phrase, “Keep Fighting.”

"[The project was to] transform spaces that were formerly occupied by racist symbols of America’s dark Confederate past into a message of hope, solidarity and forward-thinking change," the organization stated in a press release.

Courtesy Eze Amos

As protests continued in Portland, New York City and other cities across America, artists used their talents to redraw stereotypical narratives while inspiring a future of change. Amos believes that opportunities for Black photographers to work with major media houses have increased since the summer’s protests. Over the past months, he has worked with Getty Images and the New York Times to photograph the elections, COVID-19 and further demonstrations. In November, Amos and other Black Charlottesville photographers were featured in “Bearing Witness,” an exhibition at the Second Street Gallery. The collection displayed the unique perspectives of photographers and protesters fighting against systemic racism and police brutality.

“Being able to show our work at Second Street Gallery, and for it to be a group of Black photographers, that was very significant,” he said. “You know, I felt really, really very happy about that. And to see some of the young photographers coming up ... being able to showcase their work and stuff was a good thing.”

Following the death of George Floyd, the Minneapolis city council called to disband the police department. The LAPD and NYPD have plans to shift funding to youth and social services. In Louisville, the metro council voted to pass "Breonna's Law" which banned no-knock search warrants. Protests sparked change, and Hurt believes that artists should not hesitate to go out and share their message with the world.

“It's okay if it's not huge and big and doesn't change everybody's mind,” Hurt said. “If you can change one mind or reach [one person], that's pretty good … Art leads the way, even if it doesn’t seem like it does.”