Two boys sitting in a beat-up sedan, drinking out of liquor bottles as marijuana smoke hangs suspended in the air around them.

One spoke, his words sharp: “If you lived in medieval times, what would you be?”

His companion, shaggy-haired and bleary-eyed, paused. He thought for a moment.

“I’d be a king.”

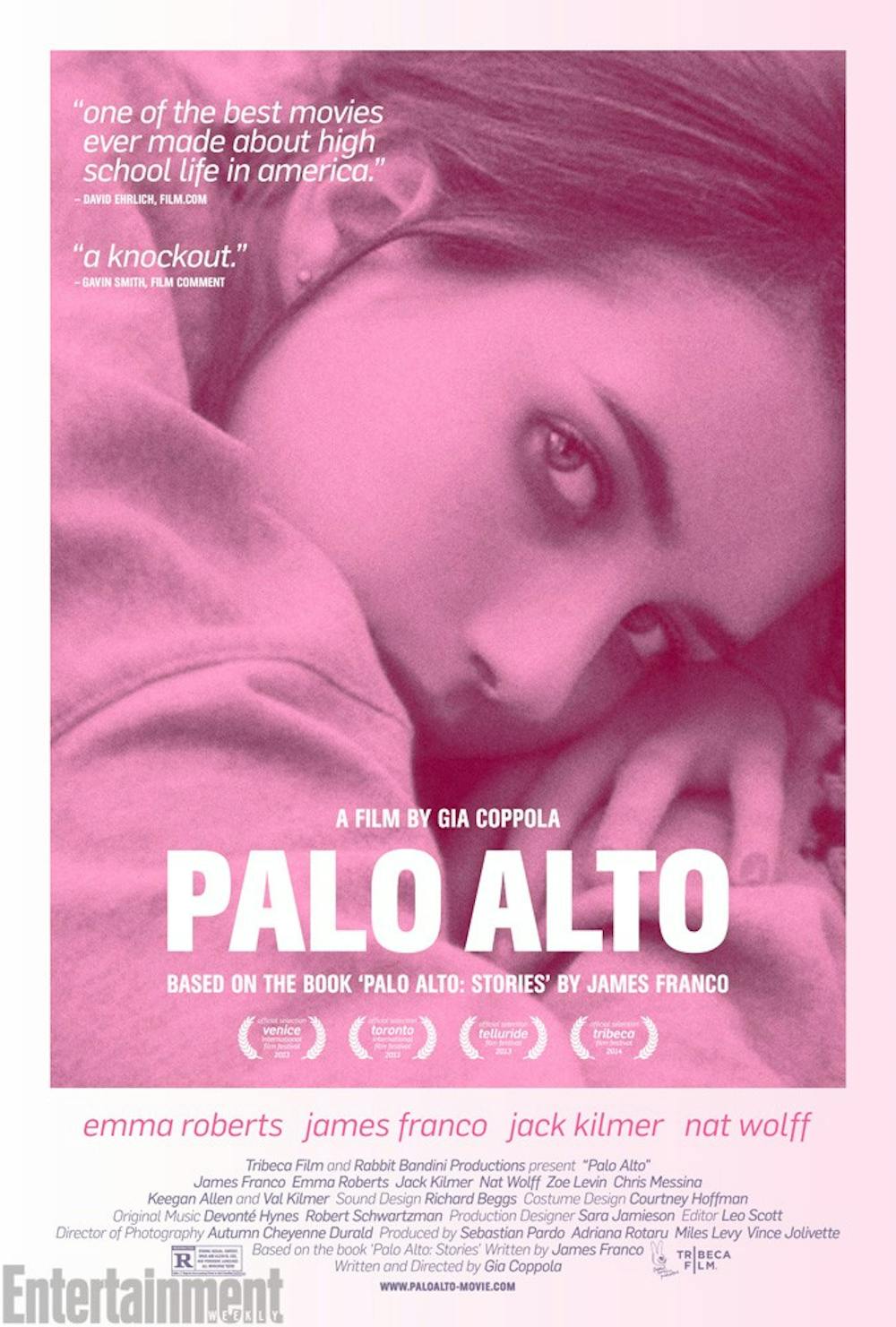

So begins “Palo Alto,” the debut film from director Gia Coppola, granddaughter of the renowned director Francis Ford and niece of acclaimed auteur Sofia.“Palo Alto” is loosely based on a collection of short stories by James Franco which detail some of his own adolescent foibles in the eponymous California town.

Franco writes in the vernacular particular to American youth: profane, angry, and whimsical, repeating phrases such as “for some reason” and “as if,” emphasizing the irrationality and dreaminess which characterize teenagers.

High school marks the beginning of a period of experimentation, one also marked by loss: loss of jejune assurance, of the clear boundaries between which we view the world.

As Franco wrote in “Halloween,” one of the stories in the collection: “Funny how new facts pop up and make you doubt there’s any goodness in life. Everyone pretends to be normal … but underneath, everyone is living some other life you don’t know about.” We no longer hesitate at the stop sign at the end of a familiar street, but press on, voracious for the “new facts,” perversely seeking that which will strip us of our faith and “make [us] doubt.”

Coppola aptly evokes this hunger in “Palo Alto,” which follows high-school students April (played by Emma Roberts), Fred (Nat Wolff), and Teddy (Jack Kilmer) as they maneuver through the temptations and travails of youth and privilege.

“Palo Alto” follows a series of suspended moments in time, each involving one or more of the three protagonists. It is far from a bildungsroman: it does not chart progress but stasis, a beautifully composed snapshot of adolescence in a suburb of Palo Alto.

One scene features long shots of shifting foliage, seen by Teddy through a car window on the way back from a probationary hearing for drunk driving. In another, April sleeps with her adult, predatory soccer coach Mr. B (James Franco) and Coppola alternates between soft blackness and vignette images of lips, a rib cage, legs intertwined, cushioned by silence and soft sighs. A third shows Teddy reading children’s books in the library which he has been assigned to for community service, regressing into a far “simpler” and purer existence, later daydreaming of frolicking with the beasts in “Where the Wild Things Are,” dressed as Max.

The cinematography is artfully done and there is no question that Coppola affirms her deserved place in the Coppola cinematic legacy. Superficially, perhaps, the film can be seen as merely another in a quickly growing genre of movies chronicling adolescent subculture. Like other movies about teenagers, it explores the confusion, recklessness, and shame concomitant with adolescence. But “Palo Alto” goes one step further: it gently but aptly characterizes the three protagonists, each serving as a complement or foil to the other.

April and Teddy are kindred souls: both reserved and confused. They know the importance of conformity but are evidently uncomfortable with what that entails. They are what many teenagers imagine themselves to be: islands of inner turmoil in the brackish sea of status quo, those who question — quietly — what Franco termed a “simple existence.”

The questions of hierarchy, of love and anger and small place in the world, are never explicitly addressed, par to form in adolescence, where all is subtext. Yet Coppola, in slow, sweeping gestures, somehow manages to urge them to the forefront. She does not pretend to give answers, but amid the frenzy and self-abuse, she also reveals the resilient presence of hope.

It is this hope that most defines Coppola’s movie: in the end, we see Fred driving into oncoming traffic, invincible king of the highway. We see Teddy walking home, having eschewed Fred’s sadism in favor of a safe distance. We see April at home, having rejected further advances from Mr. B. April texts Teddy, smiling. Teddy reads the text and smiles.

A simple existence.