As the University looks to increase its minimum wage for all full-time employees on Grounds, a variety of legal barriers may complicate that endeavor for those who are employed by external contractors rather than the University itself. President Jim Ryan announced March 7 that the minimum wage for full-time employees eligible for benefits will be increased to $15 per hour by Jan. 1, 2020.

The wage increase will cover around 1,400 full-time employees eligible for benefits across the University and Medical Center staff. Around 700 more employees who currently earn close to $15 an hour will also see an increase to their wages. The increase is also expected to have an annual cost of approximately $3.5 million with an additional $500,000 needed to make adjustments for employees who already earn between $15 and $16.25 an hour.

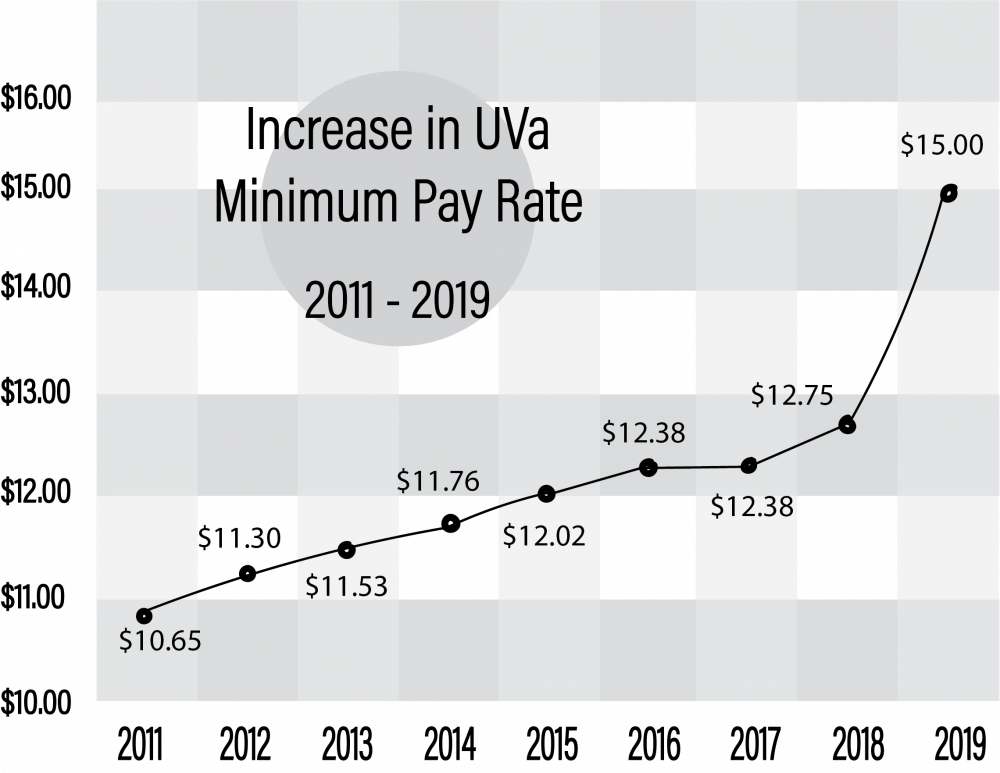

The largest employer in Charlottesville with nearly 17,500 full-time, benefits-eligible employees, the University most recently raised its minimum wage from $12.38 to $12.75 per hour in 2018 after calls from students, community members and employees. The state and federal minimum wage is $7.25.

Graphic by Tyra Krehbiel

Hannah Russell-Hunter and Corey Runkel — both third-year College students and members of the Living Wage Campaign at the University — said the wage increase was a major victory for the campaign, adding that it was the largest in the campaign’s history.

“It's a very public statement, and I think a tacit acknowledgement of the fact that students have been organizing around this for two decades,” Russell-Hunter said. “[Ryan] kind of alluded to that in his email he sent that this has been an issue at the forefront of U.Va. for like two decades, and that's how long the Living Wage Campaign has formally existed. It was good to see that people acknowledged that this is a product of community member, student and faculty organizing.”

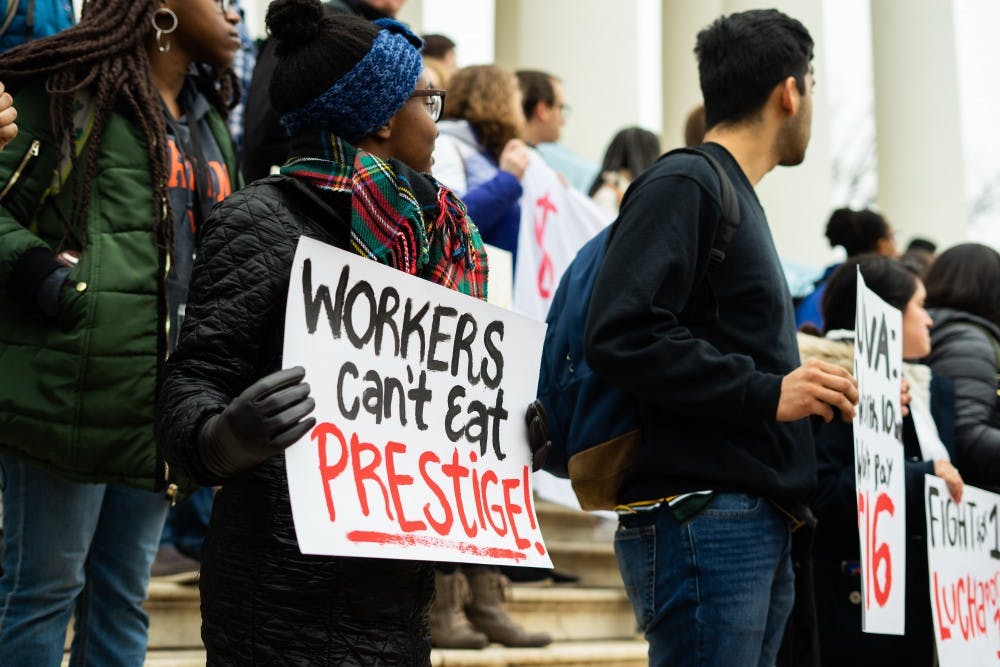

Student protesters with the Living Wage Campaign also rallied outside of a Board of Visitors meeting March 4, asking the University to implement a minimum wage of $16.84 and include contract workers in future wage increases. Russell-Hunter and Runkel added that the campaign will continue its efforts to extend the wage increase to contracted employers at the University and advocate for a $16.84 minimum wage.

Based on MIT’s living wage calculator — which estimates the living wage needed to support individuals and families based on the cost of basic necessities — a living wage in Charlottesville stands at $12.49 for a single adult or $17.16 for a family of four in which both parents work.

According to a webpage published by the University regarding the wage increase, the average University employee affected by the change lives in a two-person household — 70 percent of which the second member also works, “raising the total household income significantly.” University employees making $15 an hour will also continue to receive more than $12,000 per year in health insurance benefits and retirement contributions.

“While a $15 hourly base wage will not cover every type of household, it is above the poverty wage for every family type in our region according to the MIT Living Wage Calculator,” according to the webpage. “The MIT calculator also counts it as a living wage for single wage-earners and families living in Charlottesville and the surrounding counties with two working adults who are childless or have one child.”

However, Ryan said in his announcement that the planned wage increase will apply to 60 percent of full-time employees at the University who currently earn under $15 an hour, while the remainder are employed by outside contractors and will not receive wage increases at this time.

“Over the next few months, my team will be working on a plan to extend the same $15 commitment to contract employees,” Ryan said in the announcement. “This is legally and logistically more complicated, but our goal is to make it happen.”

Ryan added that the plan has been “heartily endorsed” by the Board of Visitors but did not further specify as to its implementation process.

In an email statement, Deputy University Spokesperson Wes Hester said cooperation with all of the University’s major contractors has been initiated.

“Work has already begun with some contractors, including Aramark, regarding how to achieve a $15 base wage,” Hester wrote. “We expect to provide an update later this calendar year.”

Legal standing: Past Virginia Attorneys General opinions side with contractors

Much of the legal difficulty that the University could face is centered around the Virginia Public Procurement Act — which dictates how public entities handle procurement with nongovernmental agencies — and a series of legal interpretations by Virginia Attorneys General in the early 2000s.

In 2002, Jerry Kilgore — at the time, the state’s Republican attorney general — wrote a non-binding legal opinion that declared localities could not require their contractors pay contracted employees any set wage amount under the VPPA, writing that “a ‘living wage’ requirement is unrelated to the goods or services to be procured” on the basis that it is a matter of social and economic policy.

Deputy Attorney General David Johnson, a deputy of Bob McDonnell — the state’s Republican attorney general in 2006 — wrote a letter to then-U.Va. Executive Vice President Leonard Sandridge, confirming McDonnell believed that the 2002 opinion was applicable to the University.

Six years later, a spokesperson for former Republican Virginia Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli said in a published statement that Cuccinelli believed Virginia codes restricted any state agencies from requiring contractors to pay a living wage.

Hester said the University plans to abide by the current legal interpretations set out in in the VPPA and by the Attorney General’s Office in 2006.

“According to an official opinion of the Attorney General that was issued in 2006, the Virginia Public Procurement Act does not allow a state agency like the University to require a contractor to pay a living wage as a condition of a contract,” Hester wrote. “Only the General Assembly can grant the authority for a state agency like the University to negotiate wages paid by a contractor.”

“While this opinion prevents us from making the payment of a living wage a condition of a contract, we will work with our major contractors to negotiate appropriate changes to our current agreements that will achieve the University’s objective,” Hester added.

Aramark — a Philadelphia-based food services contractor and the provider for University Dining Services — currently pays employees a minimum wage of $10.65 an hour. In an email statement, Karen Cutler, Aramark’s Vice President of Corporate Communication, said discussions between the University and the contractor are ongoing.

“We greatly value our employees and have always been committed to paying competitive, market-based wages, while offering a variety of benefits, training and career development opportunities,” Cutler wrote. “We will continue to work in partnership with the University over the coming months to address this opportunity.”

A new contract between U.Va. and Aramark?

As part of its current contract with Aramark, the University could be in breach of the contract or would possibly be required to renegotiate its terms of agreement if it seeks to contractually obligate the contractor to pay its employees a set minimum wage. The University has contracted dining services from Aramark since the late 1990s and most recently renewed its contract with the service provider in 2014 for a 20-year-term agreement.

According to the University's renewed 2014 contract with Aramark, “Aramark will have the capability of and be financially responsible for complying with all applicable federal, state, and local laws and regulations regarding the employment, compensation, and payment of personnel.” This includes unemployment insurance, worker’s compensation and health examinations.

The contract goes on to state that “Aramark will, in its sole discretion, determine the compensation of Aramark’s employees providing the Goods and Services to the University and be responsible for payroll taxes attributable to such compensation for each of those employees.”

However, the University or Aramark is allowed to terminate the contract at any time, provided that written notice is provided explaining why the terminating party seeks to dissolve the agreement. The contract states that each party must then engage in “good faith” discussion for a period of at least 30 days, after which either the University or Aramark may elect to terminate the agreement with 180 days prior written notice.

The University would then be required to reimburse Aramark for any remaining financial commitments it may owe to the contractor within 90 days of ending the agreement if the University chose to dissolve the contract. If Aramark chose to terminate the contract for any reason, it would be required to pay the University a $3.5 million fee if the agreement were ended between now and 2024, after which the fee would be $1 million.

The total amount of reimbursement the University would have to provide Aramark would vary based on the exact termination date of the contract, although Aramark has made a long term financial commitment of nearly $100,000,000 to the University since 2014 under the current terms of agreement. This includes a $70,000,000 unrestricted grant paid to the University by the end of 2014 and held in escrow with the purpose of funding strategic initiatives approved by the Board of Visitors. Most of the remaining funds are set aside throughout the contract period with the purpose of facility upgrades and renovations.

According to the contract, the University is also expected to receive a minimum of about $240 million in guaranteed commission from various dining services — such as dining halls, convenience stores and concessions at athletic events — provided by Aramark through 2034. By the end of the agreement, each party should also have a guaranteed profit split of at least $40 million.

Neither Aramark or the University responded to questions regarding the possible renegotiation of the current contact between the two parties.

Legal arguments for U.Va. to impose a minimum wage requirement

Local civil rights attorney Jeff Fogel said that while the University could endure a number of legal obstacles in attempting to require contractors, such as Aramark, to set a higher minimum wage, there are several legal tactics the University could employ to argue that the current interpretation of the VPPA is invalid. Fogel authored a memo to the Living Wage Campaign in 2012 which detailed the legal challenges facing the implementation of a higher minimum wage for contracted employees at the University and legal argumentation in support of its ability to do so.

Fogel said he has met with Ryan in recent months to discuss the issue, adding that he has provided administration with a copy of his 2012 memo for reference amidst its legal discussions. Fogel also said Ryan received the memo positively and shared it with the University’s Office of General Counsel.

While it is unclear if any legal action is being planned by Aramark, Fogel said the contractor could argue that the University would have no right to impose a minimum wage requirement under the VPPA and previous Attorneys General interpretations of the Act and the Dillon Rule in Virginia as requiring explicit permission from the General Assembly to set wages for contracted employees.

According to the memo, the Virginia Supreme Court reaffirmed its adherence to the Dillon Rule early in 2012 when it stated that local governing bodies "have only those powers that are

expressly granted, those necessarily or fairly implied from expressly granted powers, and those that are essential and indispensable.” It adds that the legal significance of the phrase “essential and indispensable” is often handled on a case-by-case basis.

However, Fogel cited a provision of the VPPA — which states that public bodies have the ability to consider “best value concepts” when procuring goods and nonprofessional services, such as dining employees — as a possible legal basis for allowing the University to contractually require a set minimum wage under the current contract. The Act defines best value as “the overall combination of quality, price, and various elements of required services that in total are optimal relative to a public body's needs.”

In the memo, Fogel argues that setting a minimum wage for contracted employees could be considered a “best value concept” due to its potential positive long term effects in the community, such as decreasing employee turnover, increased productivity and overall improvement in service quality as a result.

Fogel said the Virginia Attorney General’s Office could also take legal action against the University for imposing such a wage requirement but added that such an action would be unlikely to occur if the administration is seeking legal advice from the office, adding that past instances of localities mandating contractors pay a set minimum wage have been without legal ramifications.

For example, the Charlottesville City Council enacted a plan in July to raise the minimum wage for both city employees and those who currently are or will be hired as contracted employees. However, Fogel said the City, along with other Virginia municipalities, have yet to face any repercussions for the changes.

Fogel said it was important to draw a distinction between advisory legal opinions or interpretations made by an attorney general and existing law, adding that such opinions only inform legal rulings that would still have to be handed down by a judge. In the memo, Fogel writes that the Virginia Supreme Court has historically viewed attorneys general opinions as “not binding but entitled to due consideration,” meaning that if the University adopted a policy requiring contractors to pay their employees a set wage, a court could potentially rule in favor of the University if it were so challenged.

As such, Fogel said it would be in the University’s interest to pursue the policy, even if it meant losing a complex legal battle.

“Even if they conclude that the likelihood of prevailing is small they should do it — it's better to do it and lose than it is not to do it,” Fogel said. “The litigation process is also a public education process and a public relations process, and there are an awful lot of people to support the notion that people work hard to get their $15 minimum wage. So it would put additional pressure on the University … but also put some more pressure on the [General Assembly].”

Requesting a legal reinterpretation of past Attorneys General opinions?

During meetings in Richmond with Sen. Creigh Deeds (D-Bath) and Jane Dittmar in January, Del. David Toscano’s (D-Charlottesville) chief of staff, Alex Cintron, a fourth-year College student and Student Council president, inquired about the possibility of senators and delegates to issue requests for legal reinterpretation of opinions authored by the attorney general with regards to setting wages for contracted workers at the University.

Deeds said he would be willing to approach the office of Democratic Attorney General Mark Herring about a reinterpretation of Kilgore’s 2002 opinion. Deeds added that he was confident in Ryan’s willingness to address a variety of issues based on the initiatives he has spearheaded so far, even more so than previous University President Teresa Sullivan.

Dittmar said Toscano and Deeds could potentially cooperate with Student Council by drafting a joint-letter between Student Council and the lawmakers, asking the attorney general to the reconsider legal opinions of the attorneys general from the early 2000s. However, Dittmar added that such requests can often take several months to be processed, if they are even considered.

In a recent interview, Cintron said Student Council was in the process of seeking legal counsel to draft the letter when Ryan made his announcement to increase the University’s minimum wage and pursue wage increases for contracted employees. As a result, Cintron — whose term as Student Council president expires April 7 — said Student Council will no longer be pursuing the option of requesting a legal reinterpretation from the attorney general in the coming weeks but will still consider doing so in the future if deemed necessary. Cintron added that he expects to meet with Ryan soon to further discuss the matter.

Correction: This article previously stated that the University most recently raised its minimum wage from $12.38 to $12.75 per hour in 2017. It has been updated to state that the increase occurred in 2018.