Editor’s note: This article tells the story of a sexual assault.

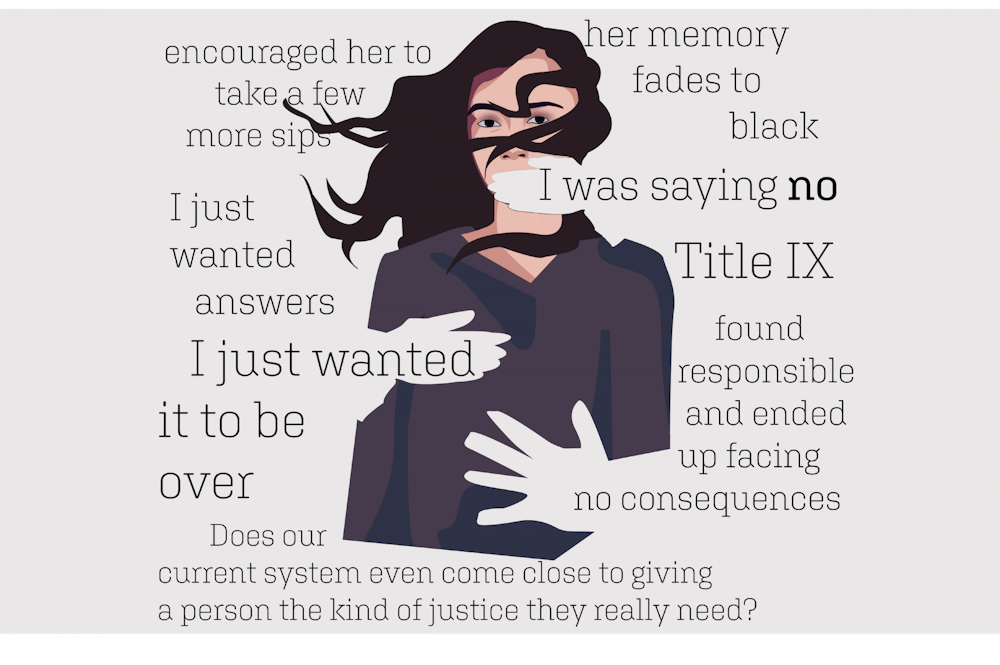

When Annaliese Estes began her sexual assault investigation through the University’s Title IX Office, she received an outline of the formal resolution process which said the investigation period typically does not exceed 60 days.

For Estes, this process took almost nine months.

These nine months preceded a painfully long summer during which a lawsuit contesting the Title IX case’s responsible finding resulted in the student who assaulted Estes receiving his degree from the University. Estes, in turn, received a three-sentence email from the Office of the University Counsel in September that read “the University’s Title IX process has concluded.”

Reading that email didn’t give Estes closure. Instead, it made her think about the course of events that led to it. The probing questions, the explaining of her story to different faces — some more sympathetic than others. The constant waiting and the helplessness that came with it. The relief at hearing the findings and believing it was over. The frustration of having that taken away.

Reporting a sexual assault through any avenue can be an isolating and traumatic experience. Title IX especially can seem like an inscrutable institution, and Estes felt thrown into a world where she couldn’t anticipate what would happen next. She wished that she had been able to read a story about what the reporting process was actually like before she started it.

That’s why she’s telling hers now.

________________________

A Charlottesville resident, she thought it would be fun if she and her friends visited the Corner bars for a night out, a fairly common practice for local kids her age.

In April of 2017, Estes was 18-years-old and a few weeks from graduating high school. A Charlottesville resident, she thought it would be fun if she and her friends visited the Corner bars for a night out, a fairly common practice for local kids her age. She said that she wanted to be more careful than usual, knowing that she would be out with strangers instead of safe in a friend’s house, and she made a mental note to stick to her drinking limits.

Her group headed to the Corner, where they immediately started mingling with University students. They met two male students, in particular, who stuck with them, even as they changed locations. As the night wore on, Estes could tell she was starting to get a little too drunk and decided to stop drinking. But shortly after, she said her friends abruptly left the bar, and she was suddenly alone — with one of the guys they’d met.

He told Estes that he would help her find her friends, but not before he picked up her drink where she had left it and encouraged her to take some more sips. And she did.

“I just wasn’t really thinking about it at the time,” Estes said. “I was like, ‘Oh, well, whatever, I’ll just find my friends soon, and then we can go home.’”

Neither of them had operable phones with them, so the student told her they could go back to his apartment where he could charge his and call his friend, who was still with Estes’ group. By this point, however, Estes was starting to feel sick — far beyond what she says she should have felt for how much she drank.

She threw up on the walk to his apartment, and she said that was the moment where her memory fades to black. The next thing she knew, she was in his bedroom, disoriented but acutely aware that she was being raped.

“It was totally dark, all the lights were off,” Estes said. “I couldn’t tell how many of my clothes I was wearing, and he was having sex with me and I was saying no.”

Estes doesn’t remember exactly how she left his apartment, but the next thing she remembers is sitting on the curb on his street, surrounded by her friends. They drove her home and put her to bed. She said she couldn’t stop vomiting.

The next morning, she went to the hospital to have a rape kit done.

________________________

The morning after her assault, Estes went to the hospital to have a rape kit done.

In the Commonwealth of Virginia, a survivor has two options for completing a rape kit. First, they can opt to do a blind rape kit, which is anonymous. The evidence collected is then sent to the Division of Consolidated Laboratory Services for storage, where it can be released if the survivor chooses later to report their assault to law enforcement. However, if the survivor wants to open a police investigation at the time the rape kit is collected, the hospital is required to immediately notify local law enforcement.

Hours after her assault, Estes hadn’t even told her parents what had happened, and she was unsure she wanted to get the police involved right away. She decided to do the blind rape kit. According to the Virginia Healthcare Guidelines for sexual assault response, this means that “evidence that would normally be collected by law enforcement may be permanently lost,” including blood or urine samples. Because she chose this option, Estes will never know if she had been drugged before her assault.

After a couple of weeks, Estes told her parents everything. She then felt like there was nothing holding her back from going to the police, so she brought her case to the Charlottesville Police Department early that summer. She talked to someone at the Victim Witness Unit, was assigned an investigator and started the emotionally grueling process of recounting every possible detail of her assault, multiple times.

When she started the police investigation, Estes didn’t even know the student’s name. The police were able to track him down through his friend who had been with her friends that night, whom the student had texted to get Estes’ friends to pick her up after the assault.

The results from the rape kit came back, and the DNA matched with his. He said that the sex they had was consensual.

After she told her parents everything, Estes decided to report her assault to the Charlottesville Police Department.

It took several months for Estes to hear from the police about the next step in her case. She was busy trying to adjust to college life at The College of William & Mary, and every time she reached out, her investigator would say that they were still working on writing everything up to send to the Commonwealth’s Attorney.

When Estes got home for summer break after her first year, her investigator told her that her case would be better served through a Title IX investigation, where the evidentiary standard is different. Title IX cases abide by “preponderance of the evidence” instead of “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Because the consequences — expulsion rather than a prison sentence, for example — are lower in Title IX cases, so is the threshold for evidence.

Estes had never considered Title IX as an option because she wasn’t a student at the University, only her assaulter was. She didn’t know that it was only necessary that the defendant in the case be a student at the University whose Title IX office investigates the assault. She said the officer investigating her case never told her. Upon learning this information, albeit a year late, she decided to bring her case to the University’s Title IX office.

In the memorandum opinion for the student’s lawsuit, written this past summer, it’s stated that the CPD officer who had been investigating Estes’ case for over a year had “failed to notify the University.” According to the opinion, it wasn’t until August 2018, when a CPD officer contacted Emily Babb, assistant vice president for Title IX compliance, and notified her of the case that the Title IX office was able to move forward with an investigation. “The University had no prior knowledge of the alleged incident,” the opinion reads.

CPD Public Information Officer Tyler Hawn declined to comment on the specific details of this case.

“It is the policy of the Charlottesville Police Department to assist sexual assault victims in a supportive manner, using appropriate victims services agencies to aid in facilitating the victim's needs, and to process crimes scenes in the most professional and proven manner to assist in the effective prosecution of said cases,” Hawn said.

A Title IX investigation into Estes’ assault was officially opened that August. The investigators talked to everyone they could who was involved in her story. The student’s friend, her friend who took her to hospital — almost everyone besides the student himself, who decided not to participate.

The 60-day rule would have given the Title IX investigators until the end of October to compile their report. They are allowed extensions, however, to accurately and comprehensively complete their investigations. Two months turned into three. Then four.

The Title IX Office finally issued the draft investigation report that December, and Estes and the defendant then had a period where they could submit their responses. By mid-February 2019, the responses were completed and all there was left to do was wait for the final investigation report to come out.

She didn’t expect that to take an additional three months.

“I just wanted an answer,” Estes said. “I just wanted it to be over.”

That winter, Estes came home from school. The stress of not knowing was too much to handle and balance alongside her schoolwork, and she felt like she couldn’t focus on anything else, much less move on, until the investigation was officially closed.

“I don’t think I ever anticipated it to come with me through almost 60 percent of my college career, maybe more,” Estes said. “So, I just went home because it was incredibly hard.”

Every day, Estes would check her email to see if the Title IX office had contacted her. And every day, her empty inbox would make her feel frustrated and alone.

“I just couldn’t understand what was taking so long,” Estes said. “They weren’t very transparent about what was happening. Every week that went by, I was like it has to be this week. There’s no way that it could be any other week. It was all I could think about.”

University spokesperson Brian Coy said that some reasons for an extended Title IX investigation can include “the availability of parties or witnesses for interviews; the availability of a party’s advisor or support person for interviews, hearings and other critical junctures; additional investigative steps requested by the parties or identified by the investigator; the opportunity for the parties to review additional information gathered during an investigation after the issuance of the Draft Investigation Report; voluminous evidence gathered during the investigation, and law enforcement requested pauses.”

Coy added that due to federal privacy laws, the University is not permitted to comment on individual Title IX cases.

Claire Kaplan, program director of Gender Violence and Social Change at the Maxine Platzer Lynn Women’s Center, said that even if the survivor completes every step in a timely manner, sometimes resistance or hesitance from the defendant can slow the investigation process.

“The University only has so much authority to make someone come in, right?” Kaplan said. “It’s things like that. It’s almost like a death by a thousand cuts. It's the little things that keep adding up, so that things drag out.”

In May 2019, the Title IX office released their final investigation report. Estes got the answer she had been waiting to hear for over two years — that the person who raped her was found responsible of sexual assault.

________________________

The Title IX formal review process is written to typically take 60 days. Investigators are allowed extensions, however, to accurately and comprehensively complete their reports.

Estes and the student were then allowed to accept or contest the report’s findings. The student contested them. A review panel hearing was set for July 1, when both parties would be able to deliver personal statements to a panel of trained University community members chosen by the Title IX coordinator and the final sanction would be given. Depending on the outcome of the hearing, the student’s degree could be revoked or withheld temporarily.

The release of the report happened to coincide with the student’s graduation. He was allowed to walk the Lawn but was told his degree would be pending until after the hearing.

Estes began preparing for the hearing, drafting her impact statement and looking forward to this painful period in her life finally coming to an end. Then, the student’s lawyers called her team and said that they were planning to sue the University, on the basis that the student’s right to due process had been violated during the investigation.

His lawyers said that if Estes settled with them and chose not to participate in the review panel hearing, she would receive a settlement, he would never move back to Charlottesville, and if he returned briefly for an alumni event, she would be notified that he was in town. She and her family debated taking the settlement but decided to reject the offer just a few days before the scheduled hearing.

“It could have almost paid for the two years of college that were such a struggle for me, which almost felt wasted because I wasn’t able to devote myself as much to my classes as I wanted to,” Estes said. “So it totally has value, but I just think for me, and for my healing process, I felt like if I do this, and if I don’t go and don’t advocate for myself at this hearing, and I never know what might have happened — I just couldn’t do it.”

The night before the hearing, however, Estes found out that it was being postponed indefinitely. The lawsuit, which was against the University, the Board of Visitors, the Title IX investigators and University President Jim Ryan, was opened and went to Judge Glen Conrad, senior judge for the Western District of Virginia. The student’s lawyers had filed an emergency injunctive relief to halt the review panel hearing’s proceedings pending order of the court, which Judge Conrad granted.

The lawsuit continued through July and August. Then, a member of the University's counsel asked to meet with Estes. She says he told her that Judge Conrad had made it clear he was going to rule in favor of the student and have the University confer his degree. Beyond that, Estes said the counsel told her Judge Conrad would rewrite elements of the University’s Title IX policy in his ruling.

“The lawyer from U.Va. said that, being someone who understands U.Va.’s Title IX policy, that seeing how it works daily, the idea he got from what Judge Conrad wanted to rewrite it to would make it totally unworkable for the scenarios that it’s used for,” Estes said. “It would just totally take U.Va. multiple steps back. So, it was really worrisome to him and because of that, he felt that he had a greater obligation to protect U.Va.’s Title IX policy, whereas they usually would have just prioritized my specific case.”

Judge Conrad’s office did not comment on this particular claim, and declined to comment separately from what he had written in his opinion. The University’s Office of the General Counsel also declined a request for comment.

In his opinion, Judge Conrad wrote that the student, who had a job lined up for the fall that was contingent upon him receiving his degree, could face “irreparable harm” should the University expel him or suspend his degree.

“Based on the terms of the Title IX Policy and Procedures, Doe has a colorable argument that the University does not have authority to discipline him for the alleged incident involving Roe,” the opinion reads. “The incident occurred off campus on private property, and the investigation confirmed that Roe is not a student or employee of the University and that she is not ‘otherwise seeking access to any University program or activity that was interfered with by [Doe’s] alleged conduct.’”

He wrote that while Estes “may have a legitimate interest in the finality of the Title IX process, the timeframe for completion of the investigation has already lasted far longer than the typical 60-day period set forth in the Title IX Procedures, and the University has not offered any explanation for the delay.”

“Any prejudice or inconvenience” to Estes, he added, would be outweighed by the potential consequences for the student if the review panel hearing proceeded.

The University ended up settling in court, so there was no need for Judge Conrad to make a further ruling in the case. The student received his degree, the investigation was closed and on September 11, Estes received that three-sentence email from the Office of the University Counsel. She never received the investigation’s final outcome letter, which would have detailed all of the findings and sanctions. In fact, she never heard from the Title IX Office again.

________________________

Looking back at everything that unfolded over the past two and a half years, Estes is tired.

“I’ve gone through almost every route of reporting that’s available, and here I am at the end and nothing really happened,” Estes said. “The fact that they said this reaches our evidentiary standard, we think there’s enough evidence to say that it’s likely he committed sexual assault, that he violated our Title IX policy, and then still, after all that, just give him his degree anyways and just not say a word about it.”

Kaplan said that she has never been involved in a case where the defendant was found responsible and ended up facing no consequences. She is, however, all too familiar with cases where survivors feel that the consequences their assaulters end up facing are inadequate. She said it can be difficult to find a sense of justice when that happens. It comes down to the question, she says, if there even is a sanction that can address a crime as personal and emotionally debilitating as sexual assault.

“Does our current system even come close to giving a person the kind of justice they really need?” Kaplan asked. “And, dealing with the person who committed that crime, who is still among us — even if they’re not at U.Va., they’re still in the world — how do we deal with those people so they don’t do it again? I don’t see our system as being very effective in that way.”

It’s hard for Estes not to feel discouraged, especially as she still feels a severe lack of closure over how her investigation ended.

“I just felt very betrayed by the process,” she said. “Especially because I was promised that there would be a final letter detailing the findings and the sanction, and that’s not even what I got, it wasn’t even that.”

She and her lawyers think that some kind of confidentiality agreement was included in the University’s settlement with the student’s team, which is why she never received that final summary. Maybe reading it wouldn’t be able to change anything, but Estes wonders if it would make it easier to move on.

Universities should treat sexual assault cases with more gravity, Estes says. She thinks that the culture is slowly improving — she still has hope after all of this. But she thinks the outcome of her case doesn’t reflect the values or ideals of this school that emphasizes its commitment to honor above everything else.

“Especially because this is such a prestigious university, holding a degree from here is such an honor,” Estes said. “Allowing predators or rapists to walk free or go with little to no sanctions devalues that degree. It really does. More than that, it just kind of tells survivors, ‘We believe you, but it’s not really that bad.’”

Estes thinks that increased transparency within the institutions dealing with sexual assault cases is necessary to improve the reporting process. For example, if she knew more about her initial options, she might not have felt so overwhelmed at the hospital that first day after her assault.

“I had no idea when I went to the hospital that there were different levels of reporting that I could do there, and it would affect down the line what could be proven and what was just speculation,” Estes said.

Having her story available for other survivors to read and learn from, Estes believes is one step toward that transparency. Nothing can change, she thinks, until people commit themselves to bringing this issue out into the open, little by little, and finally start talking about it.

Graphics by Tyra Krehbiel.