According to the 2020 National Diabetes Statistics Report, 34.2 million people suffer from diabetes in the United States, and around 90 to 95 percent of these cases are classified as Type 2 diabetes. In an effort to regain health, most T2D patients will either try to lose weight or become encumbered by increasing doses of medication. However, effective T2D management may not be limited to costly prescriptions or weight loss. In fact, University researchers have developed a more progressive management program — one that promotes patient empowerment in lifestyle choices.

While patients who are diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes are unable to produce insulin in their pancreas, patients with T2D are often resistant to insulin as lifestyle habits alter the body’s reaction to glucose, leaving their bodies unable to properly metabolize it. As a result, blood glucose levels in people diagnosed with T2D can climb until they reach levels of toxicity that harm the nervous and cardiovascular systems.

Overweight patients may also experience pancreas damage due to an abnormal amount of adipose, or fat tissue, in their abdomen. This damage further impairs insulin production, indicating a correlation between obesity and T2D — this is why many patients diagnosed with T2D are advised to lose weight as part of treatment. However, some patients cannot lose weight and others do not want to, so if a weight-loss lifestyle cannot be easily implemented, then a patient can opt for medication such as Metformin, a drug that treats high blood glucose.

Yet, a medication lifestyle also invites complications. The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study found that T2D patients produce incrementally less insulin on an annual basis, and as a result, often need higher and higher doses of medication the longer they have the disease. This scenario not only leads to additional financial obligations and resulting non-compliance regarding the prescribed medication, but can also culminate in a patient being dependent on insulin for life.

Evidently, T2D treatment and prevention can be difficult to manage. Despite this, Daniel Cox, professor of psychiatric medicine and internal medicine, sensed some potential in the predicament after he developed T2D himself.

Initially, Cox’s blood glucose levels were high, which was confirmed by detecting high levels of glycosylated hemoglobin, HbA1c. While blood glucose levels vary during the course of a day, particularly in association with meals, HbA1c levels more accurately reflect blood glucose levels by measuring the amount of glucose bound to hemoglobin over a three-month period. The more hemoglobin A1c detected, the higher the glucose levels over the past three months.

“A person who doesn’t have diabetes has an A1c of 5.6 or below … and a person who has diabetes has an A1c of 6.5 or higher,” Cox said. “My A1c was 10.6.”

Anthony McCall, Cox’s endocrinologist and medical research professor, advised him to start Metformin right away, but Cox had another idea in mind.

As a researcher, Cox had been working on diabetes for over 30 years, and he knew that in order to lower his A1c level, he had to learn how to quickly reduce his blood glucose and prevent it from spiking again. He also knew that he would not be able to lose weight easily, so he decided to focus on reducing his carbohydrate consumption and sedentary behavior while implementing an achievable and regular exercise routine.

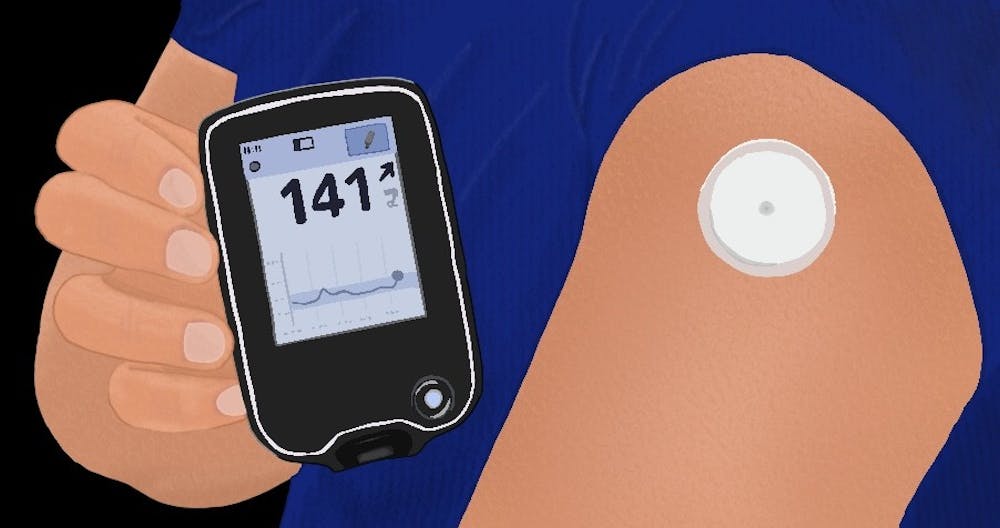

High carbohydrate intake can cause blood glucose levels to rise rapidly after a meal. To understand which carbs specifically spiked his levels, Cox used the Continuous Glucose Monitor. Unlike a blood glucose meter, which requires a patient to prick their finger to determine glucose levels, the Continuous Glucose Monitor consists of a device that scans a sensor attached to Cox’s arm and produces a graph of his recent blood glucose levels.

With this, Cox has immediate access to his blood sugar history and a better understanding of how to move forward. He can also experiment. For instance, he knows that an IPA beer will not affect his blood glucose, while a porter will, merely by checking his monitor after consumption.

Cox created a personal goal of going to bed with a blood glucose level lower than 130. If his monitor reads 140 after dinner, he grabs his earphones and heads out for a neighborhood walk, as activating his skeletal muscles burns glucose and temporarily reduces his insulin resistance.

Eleven years later, Cox has neither made the transition to medications nor has he worried about losing weight. But what he has done is organized the Glycemic Excursion Minimization, a program that allows other T2D patients to experience his same success.

“This radical new treatment program is actually quite simple,” Cox said.

GEM aims to educate, activate and motivate patients by enhancing their understanding of personal blood glucose levels and equipping them to make lifestyle decisions in response.

To test the efficacy of GEM, Cox and McCall directed a clinical study in which a population of T2D patients were divided into four groups — one of which was given weight management training and three of which received 4-6 week lessons.

According to the study, the lessons, or “didactic sessions,” educated patients with feedback from the Continuous Glucose Monitor, eliminated the consumption of high-carb foods, increased physical activity and promoted lifetime food, activity and relapse management.

The researchers found that the participants who attended the lessons actually experienced more weight loss than the group that received weight loss training. Additionally, the study reports that these patients left with improved diabetes knowledge and an enhanced quality of life.

At a one-year-long follow up, the A1c levels of the didactic groups were still lower than that of the weight loss group.

“That difference [in A1c levels between the groups] was not quite as big as [it was] originally,” McCall said. “But it was still improved over what was the typical standard of care.”

The researchers’ vision for T2D patients is one of empowerment and choice. Although there may be no one specific treatment advised for diabetes, according to McCall and Cox, patients withhold the power to manage their health in ways that even doctors cannot control.

“Diabetes is a self-treating disorder,” McCall said. “The last thing you want is a physician treating diabetes — ‘It’s whatever you say, doc.’ No, it’s not whatever I say — it’s what you do, what you want to do.”