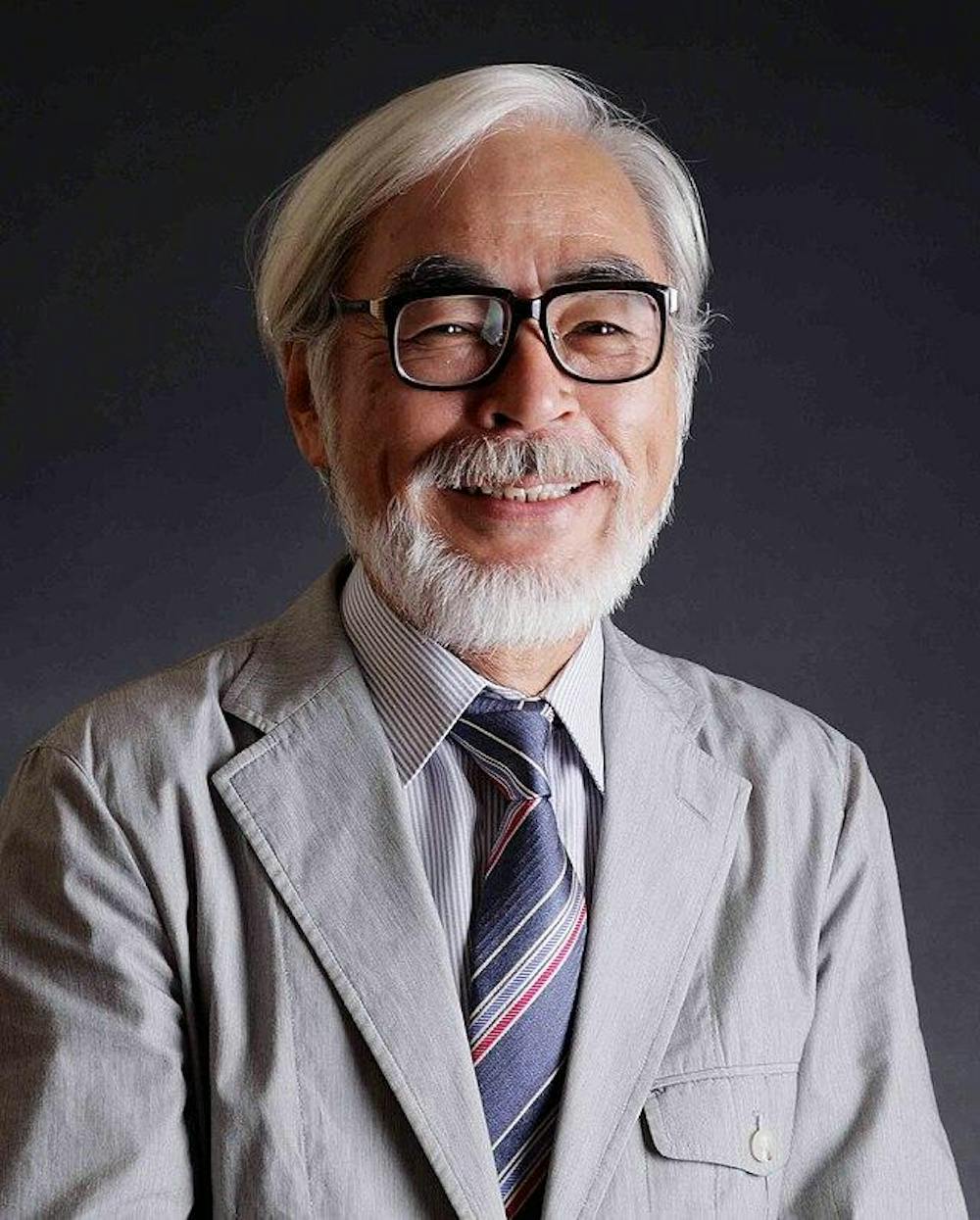

Like his iconic production style, where storyboard animations often precede set scripts, legendary filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki is unpredictable. While announcing his retirement in 2013, Miyazaki — Tokyo native and co-founder of internationally acclaimed animation company Studio Ghibli — has since returned to the spotlight several times, most recently with “The Boy and the Heron,” hitting U.S. theaters last Friday.

In preparation for the record-breaking North American release, the original Japanese dialogue was dubbed into English by voice actors, including Robert Pattinson, Florence Pugh, Christian Bale and Gemma Chan.

While the star-studded cast draws in viewers, it is the breathtaking visuals and gripping storyline that retains them.

“The Boy and the Heron” follows a young protagonist named Mahito — voiced by Luca Padovan — in the wake of tragically losing his mother in a Tokyo fire during the Pacific Theater.

Mahito, who is partially based on Miyazaki’s boyhood, must move to an ominous countryside estate with his industrialist father and his new wife, Mahito’s aunt, voiced by Chan.

There, the boy is hectored by a talking heron, who insists that his mother is still alive. After his aunt goes missing, Mahito and the estate’s nicotine-fiend housemaid are lured into a nearby tower, where the typical Miyazaki magic begins.

Mahito is swept to a beautiful but dangerous world at the intersection of life and death, and must embark on an adventure to find the people he loves, and himself in the process. Ultimately, he must choose between staying in the timeless realm of new beginnings and returning to a reality of pain and insecurity.

Mahito’s journey transcends space and time, launching into a boundless, yet intimate adventure for a grieving boy struggling to come to terms with his place in the world.

In “The Boy and the Heron,” Studio Ghibli once again transmits viewers into a fantasy world beyond comprehension while advancing themes that are firmly grounded in reality. The film continues the studio’s precedent of confronting mature themes through many emotional moments, even including a striking instance of self-harm.

A further manifestation of the themes is depicted in Miyazaki’s signature nonhuman characters. Bouncy marshmallow-esque creatures called warawara represent the souls of future lives, threatened by hungry pelicans — misunderstood wardens of death and emblems of unrealized potential, forced to play their role by the realm’s deity.

The stakes are magnified by the pursuit of the brutish and greedy parakeets, led by the Parakeet King — voiced by Dave Bautista — who challenges for command of the realm with his horde in a blind grasp for power.

Viewers may be surprised by the curious dynamic between the protagonist and the heron, who shifts from a powerful, off-putting presence to a cranky quipster sidekick with relatively unpleasant human-like qualities. The relationship between the two grows to one of mutual dependence and understanding throughout the film, guiding the events of the story and giving Mahito an equal that has long eluded him.

Though the film’s English presentation was optimal, the translation had some naturally awkward phrases. These were unavoidable, but can certainly irk the hypercritical ear.

Further, with the over two-hour runtime, the film's pace lags due to the delayed onset of Mahito’s magical adventure. The best use of this time would have included contextualization of the relationship between Mahito and his mother. However, significant emphasis is placed on Mahito's grief, without the audience truly empathizing with the character yet.

The later portion of the film, though, brings more than enough flair to win over potential critics. In what is likely Studio Ghibli’s most magnificent production visually, the film’s stunning animation and color contrast invite an awestruck audience into the realm in a perfect display of the powerful nature of hand-drawn animation.

Despite the success of “The Boy and the Heron,” there’s no time to gloat for Miyazaki. The director, soon to be 83 years old, is already absorbed with his next work, leaving Studio Ghibli fans eagerly anticipating what’s coming next.

For now, viewers can enjoy “The Boy and Heron's” enthralling tale of life with transparent portrayals of discomfort coupled with head-spinning beauty and meaning — an emotional overview of self-discovery from a perspective worth seeing.