To celebrate the 100th anniversary of the American artist Joan Mitchell’s birth, museums all over — such as the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Museum of Modern Art and the Seattle Art Museum — are displaying collections of her work. However, along with celebrating the artistry of Joan Mitchell, the Fralin Museum of Art exhibit also centers the process of restoring the artwork itself.

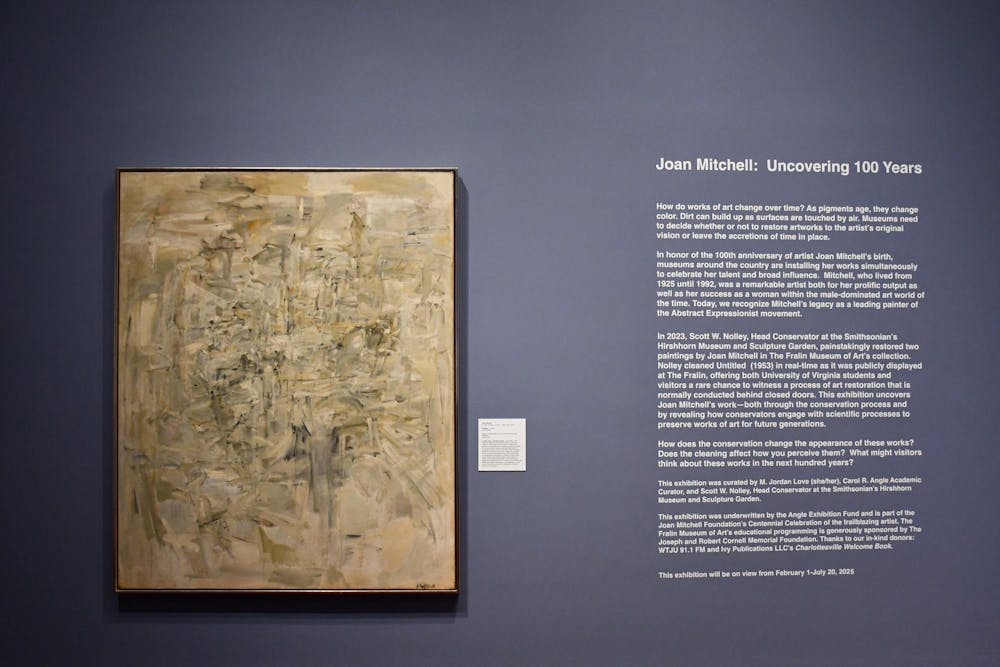

Unveiled 10 days before Mitchell’s birthday on Feb. 2, the multimedia exhibit displays five pieces of her work — two that have been restored, and three that have not — along with a video showing the process of art restoration.

Known best for her abstract expressionism, Joan Mitchell is one of the most influential contemporary artists, with her career spanning from the 1950s to the 1990s. Abstract expressionism is a mid century art movement characterized by its emotion-based perspective of the abstract movement. Joan Mitchell pioneered a spot for women in this originally male-dominated art movement, producing numerous acclaimed pieces throughout her life.

M. Jordan Love, Carol R. Angle academic curator at the Fralin Museum of Art, explained that due to the way in which the Fralin highlighted abstract artists in its 2023 exhibit “Processing Abstraction,” the museum wanted to take a different approach to Joan Mitchell’s works. They asked Scott W. Nolley, Head Conservator at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum, to restore several Mitchell paintings already in the Fralin’s collection.

“We had talked about her as an artist and her work as part of the abstract painting movement,” Love said. “We hadn’t told the conservation story.”

The exhibit utilizes a mix of Mitchell’s painting from the late 1950s that Nolley has restored and pieces that have accumulated grime from general daily life. Most of the pieces displayed in this exhibit were donations from Alan Groh, an alum of the University and close friend of Mitchell. With most of these pieces being gifts that were stored within the homes of Mitchell’s good friends, the environment around these paintings contributed to their decline. The paintings had been found to have traces of cigarette smoke, wine and soot from chimneys.

Second-year College student Saba Nasseri noted the environmental decay aspect during her walkthrough of the exhibit.

“I thought the whole exhibit was pretty cool,” Nasseri said. “How certain particles in the surrounding area can kind of impact or degrade the artwork and how that could possibly alter how people view it in 10 years.”

The paintings are displayed along the wall of the second floor of the Fralin, with the two larger paintings having their own wall and the three smaller pieces occupying the same wall. Facing directly across from the entrance and situated next to one of the larger paintings, there is a large block of white text which describes the exhibit while also presenting questions for the viewer to consider.

One question asks the viewer if the restoration of these pieces affects how they are perceived. By posing these questions, the viewer is drawn towards the conservation story of how these paintings have undergone changes in addition to admiring these works. These questions led Nasseri to take a new perspective.

“If the art of preserving a piece of art itself, if that is technically altering the artwork from its original state — should it continue to be done, even if it is changing the artwork?” Nasseri said.

Ainsley McGowan, president of the Fralin Student Docent Program and third-year College student, said that the student docent program was able to speak to Nolley about this process, delving into the complex nature of the work.

“Every little piece of the painting can use a different chemical for cleaning,” McGowan said. “How far [do] you go with conserving?”

According to Love, the Fralin’s smaller size organizationally means that while the exhibit is limited, the Fralin was able to explore the more intricate details that go into the restoration of these paintings.

“Universities and colleges are kind of uniquely positioned to be able to do kind of pop-up exhibitions like this,” Love said. “It’s great for us to do that, and to be able to have these small focused shows.”

Love went on to explain that the process of restoring paintings works on a case by case basis with the amount of restoration differing based on the desired outcome. She said that some paintings only require minor tweaks to stop them from deteriorating. But some curators want restorations to restore paintings to their original visual look.

“It’s kind of usually some sort of combination, conservation and restoration, you have to find that happy middle ground,” Love said. “So it really depends on what your goal is, what the damage is, and then you find that middle ground that makes sense.”

Paired with a video that portrays Nolley discussing the intricacies of restoring a piece of art, the exhibit highlights how restorations to these works happen on a molecular level. In the case of “Untitled” (1953), Nolley utilized a surfactant system by using a chelator — an organic cleaner — to clean the painting, which had been covered in a layer of cigarette smoke. Through this technique, Nolley revitalized the integrity of the painting without compromising the paints originally used.

In taking this perspective on Mitchell’s work, the Fralin is opening up new avenues of learning about conservation. Love hopes that one day more interdisciplinary classes come to view these exhibits and learn about these processes.

“My goal someday would be to get more chemistry classes [to visit],” Love said. “We can make professors and students realize there’s a lot of intersections.”

According to McGowan the intersection of art and science is not a new idea within museum spaces.

“I think a lot of museums are moving more and more towards that art can connect with the hard sciences,” McGowan said. “You don’t have to choose one or the other, and you never really have had to choose.”

“Joan Mitchell: Uncovering 100 Years” is at the Fralin until July 20. The Fralin Museum is always free and open daily except Monday.