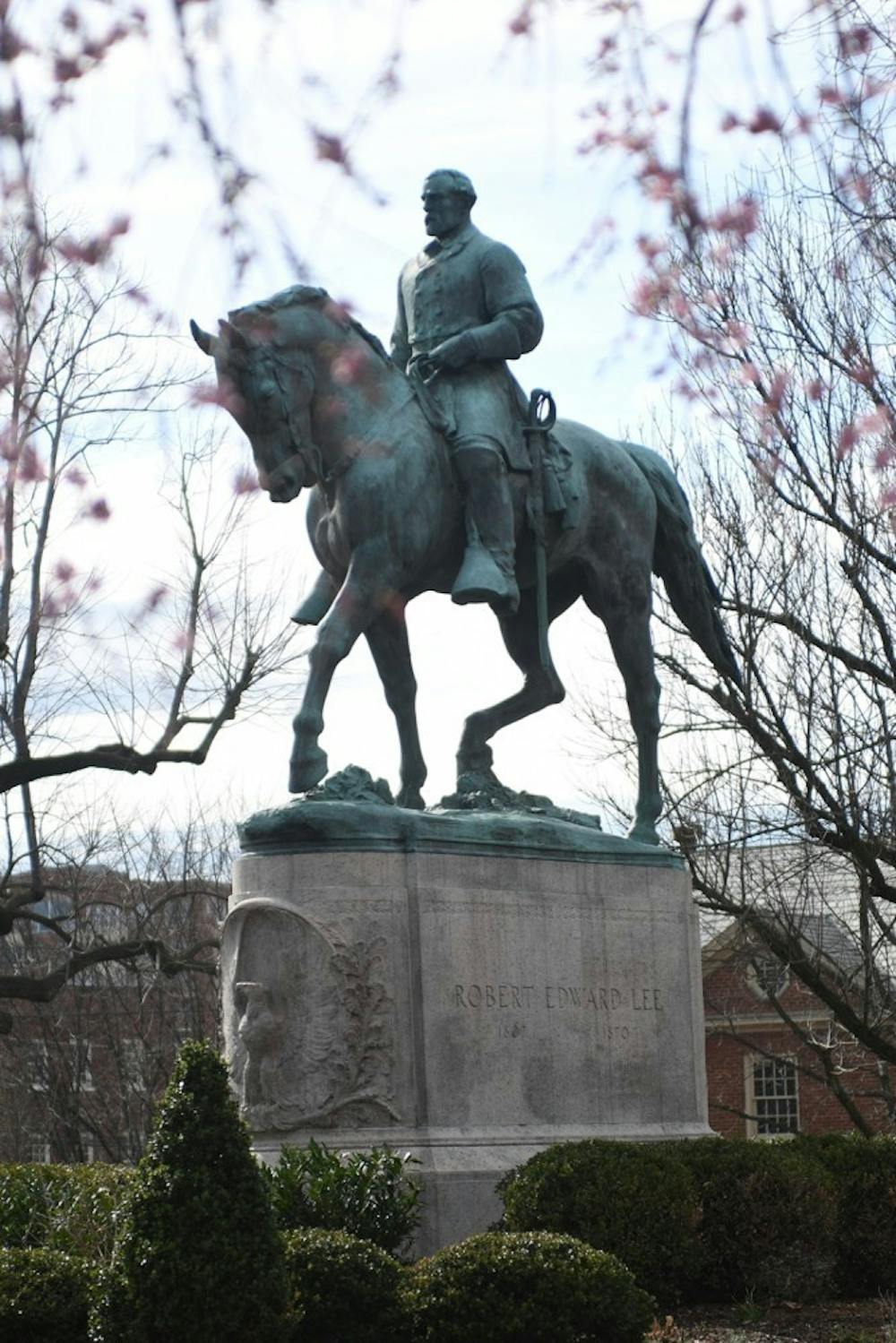

Until recently, I was utterly oblivious to the immense size of Charlottesville's Robert E. Lee statue. In my imagination, the statue stood at a height slightly more than my own five feet eight inches. Turns out, the Lee statue stands at a massive twenty-six feet. That’s marginally shorter than a two-story building, and more than four times as tall as I imagined.

Over the past several months, I have spent long hours studying the history and the ideology behind the Confederate statues. As a quote-unquote outsider, it was difficult for me to fully understand the many layers of history, and perhaps more importantly, politics, that constitute the issue of potentially moving these monuments. In all my wading through mountains of historical documents and contemporary op-eds, academic papers on architecture and psychological analyses of conflict resolution, it never occurred to me to pull up an actual photograph of the General Lee statue till I was well into my research. When I finally rectified my error, it became clear to me just how fallacious I was in my estimate of the statue’s immensity.

The massive size of Confederate statues is exactly why we can’t leave them where they currently stand. In the 21st century, even if we claim to have long moved past the principles on which the Confederacy was founded, the massive physical presence of Confederate statues remains an effective reminder of the Confederacy's secession from the Union and crusade to preserve the institution of slavery. Great care was taken to ensure that these monuments evoked a favorable interpretation of the people they represented, and more importantly, of the ideals they sought to advance. By the sheer act of existing in a space otherwise deemed public, Confederate statues are able to create a setting that is necessarily exclusionary. Such exclusion, as Stephen Clowney from the University of Arkansas points out, seeps into the economic and social life of a community, so that African-American people are kept from accessing important resources and avenues for growth. The effects of such exclusion are dire and immediate and must be addressed as soon as possible.

However, completely destroying these statues is hardly an appropriate solution. Confederate statues are an upsetting but integral part of American history. The fact that they continue to stand is an important reminder of not just this history, but also the fact that not everyone in the South has yet given up on the ideals of the Confederacy. To get rid of the monuments completely would be to brush these issues under the rug.

The foremost solution that has emerged is to put Confederate statues in museums. While the proposal has been largely well received, it has one rather interesting opponent — the Smithsonian. In writing for the Smithsonian magazine, Janeen Bryant and her colleagues cite the apparent failure of mainstream museums to effectively re-contextualize problematic artifacts in the past.

What Bryant and her colleagues say is true — historically, mainstream museums have been complicit in the erasure of the histories of people of color. However, one may argue that this moment in history is different from the ones before. There are political undercurrents to move Confederate statues and to acknowledge and make explicit America’s racist past that weren’t a part of the conversation before.

The evidence for such momentum is clear. The Unite the Right rally on Aug. 11 and 12, 2017 in Charlottesville was hardly an isolated incident — similar rallies have taken place in Richmond, Virginia and at the University of North Carolina. There is a growing movement to finally reckon with the narratives extended by the Confederacy, and by the people who continue to venerate its “heroes.” This is enough to provide the political capital needed to hold museums accountable if they fail to re-contextualize Confederate statues in a way that is effective.

The sheer size and continued existence of these statues in public places are hugely relevant when it comes to how the movement moves forward. At the beginning of the summer, a Virginia judge ruled that the city of Charlottesville could not remove the Lee statue since it was protected by virtue of being a “war memorial”. However, what’s worth noting is the fact that many Confederate statues, including the one in Charlottesville, were constructed many years after the Civil War and Reconstruction. The Lee memorial, for example, was constructed in 1924, during the Jim Crow era. As Miles Parks notes in writing for the NPR, the fact that these monuments were constructed so long after the Civil War and in the midst of great social and political change lends to the argument that these were meant more to mark problematic ideology than benign respect for military heroes. As the country made strides towards a more equal society, the South reminisced the good old days of the Confederacy. If what these statues remember isn’t a war at all but an ideological nostalgia, can they still be considered war memorials?

Virginia needs to reckon with what it considers war memorials, and perhaps add conditions to the state law to ensure that racist monuments are no longer protected against removal. One criterion to consider adding could perhaps be a time limit on how long after a war the memorial had to have been constructed. The Lee statue was constructed just under 60 years after the end of the Civil War, closer to the March on Washington than the Civil War. The intention behind Confederate monuments was never benign remembrance, but targeted messaging. Almost two years after the Charlottesville rally, let’s put an end to it.

Devyani Goel is a second-year undergraduate student at Columbia University.