After years of planning and months of construction, the University will unveil The Memorial to Enslaved Laborers in April 2020.

While the memorial won’t open publicly until spring, the University will hold a private event in December for the descendants of the enslaved laborers for an initial viewing.

Efforts behind the memorial began in 2010, and since the fall of 2016, the University has been working with a selected design team while gathering community input to determine the structure and location of the memorial.

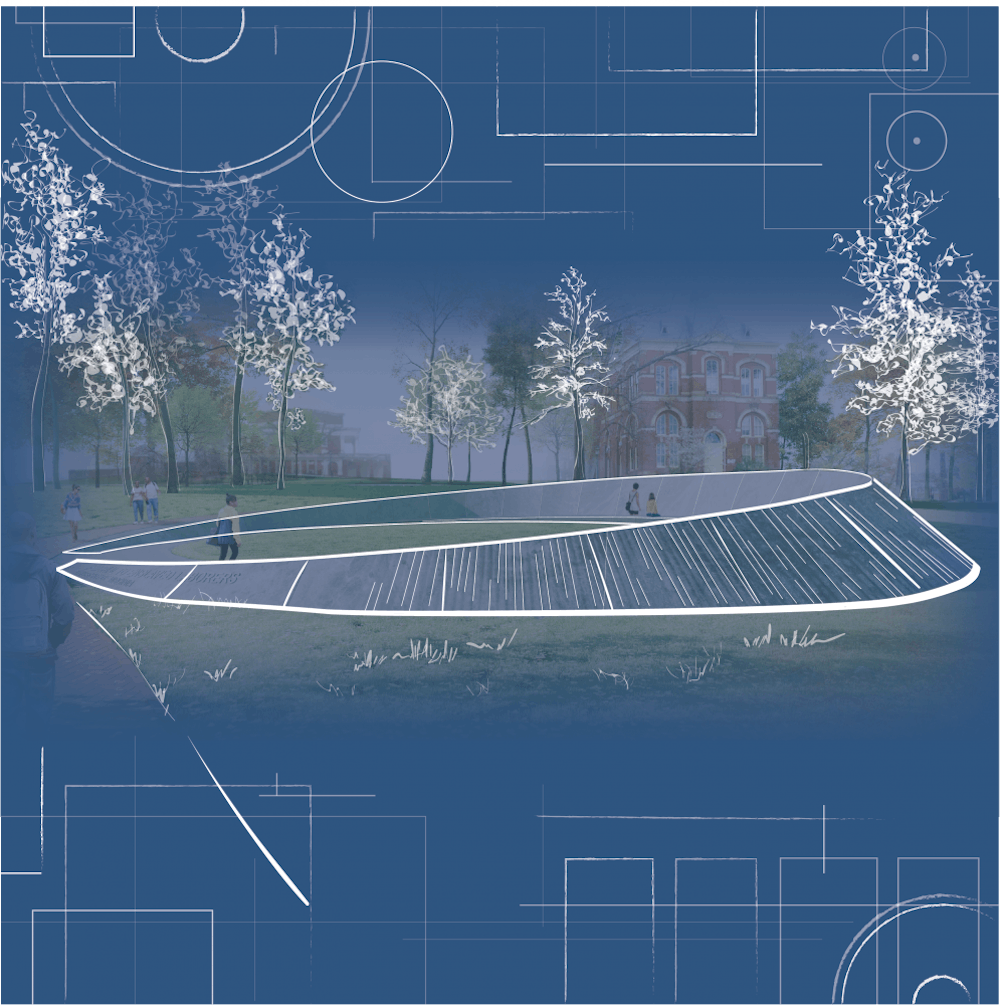

The resulting monument, which began construction last fall, intends to honor the 4,000-5,000 individuals who built and maintained the University for four decades of enslavement and to be a step toward reconciliation with the University’s past.

The President’s Commision on the University in the Age of Segregation, which is in charge of the memorial project, has paired the memorial with the task of finding and contacting descendants of the enslaved laborers that built the University.

According to Kirt von Daacke, co-chair of the Commission and assistant dean and professor of history in the College, a large portion of the Commission’s work has been community engagement with University students and faculty as well as with Charlottesville citizens.

“The Commission … was always really interested in connecting to descendants and connecting to the community, but we had to build the relationship,” von Daacke said. “We weren’t at the point where, as representatives of the University, we could rightly go out and say, ‘Hey we’re looking for descendants, we want to tell your story.’ We first had to do the hard work of what is our story.”

To assist in tracking descendants, the Commission hired genealogist Shelley Murphy as the descendant project researcher. Her role is to use the list of enslaved laborers at the University between 1818 to 1866 to draw connections to descendants today.

According to Murphy, each name requires a lot of research, but she has so far been able to craft about 40 ancestral trees in an attempt to form these connections.

“I’ve had great progress and interactions so far,” Murphy said. “People are sharing information with me, and we are able to work on their trees because there could be brick walls, like they might not know their ancestors, but they may have the same surname or location or area, so we track it back using local, state and federal records.”

According to Murphy, the majority of descendants she has contacted are grateful that Murphy can help them fill gaps in their history or connect them to ancestors of whom they were otherwise unaware.

Since the family trees can become complicated and require a lot of research to find a present-day connection, Murphy doubts she will be able to work through every name by December. The Commission hopes to extend the project in order to continue making connections with descendants, but, as of now, Murphy is only hired until December.

Murphy can research descendants and work on building their family trees either starting from the white family or the enslaved laborers. However, she has found lines can often intersect and make building connections more difficult.

“Some of these ancestral lines are connected to other lines, because these slaves were basically rented to the University for the work that was done,” Murphy said. “To my knowledge, the University only bought and owned one slave.”

The Commission has created a Facebook page for the project as well, titled “Finding the Enslaved Laborers at UVA.” People are encouraged to reach out to the page if they believe they may have an ancestor who was an enslaved laborer at the University.

According to Murphy, the Commission’s purpose behind contacting these descendants is to invite them to the private event for the memorial in December as well as for Murphy to help them piece together their family history.

According to von Daacke, the memorial is currently 65-70 percent completed and is on track to be finished in November. However, the University decided to wait until April to publicly unveil the memorial due to weather concerns and potential exam complications during the winter.

The Commission’s focus on community engagement also can be seen in the location of the memorial. According to von Daacke, students and faculty originally asked for the dedication to be on the Lawn, but Charlottesville community members wanted a more accessible location.

The memorial’s current location was chosen because it is both part of the historic fabric of the University and can be seen from and accessed by the larger Charlottesville community.

The memorial “is just an object, but there are a lot of objects like this around Grounds; they tell very different stories,” von Daacke said. “We’ve been working on renaming buildings, putting interpretive panels and bringing to light those spaces that can tell the story. But how do you talk about 4,000 people and their experiences?”

Currently, Holsinger portraits — which are studio portraits of African-Americans taken during the Jim Crow era of racial segregation— are hung around the fence of the memorial site. They represent African-American community members representing themselves in the way they chose, rather than being defined by stereotypes, oppression and racism.

The portraits’ purpose on the memorial’s fencing is to show that “the story the monument begins to tell does not end in 1865,” and the Commission hopes to find somewhere to install them when the fencing comes down, as they will not be part of the actual memorial.

“It’s been really powerful to see those pictures up there,” von Daacke said. “I’ve met people standing in front of their own ancestors taking photographs.”

According to von Daacke, the memorial is a step in the right direction in the University addressing its past and better addressing the history of slavery on Grounds.

“It’s important [for] signaling that the University is making a permanent change to the landscape,” von Daacke said. “If all your buildings are named after white men who went to the University, you’re not telling a really full story about who you are … I think you have to do a lot more, that’s [the memorial] not enough in and of itself, but it’s a start.”