Infusing the Fralin with captivating illustrations of familiar childhood tales, “Figure and Fable: Aesop Through the Ages” dives into a world of Aesop’s fables — the exhibit is a compelling collection of various authors and artists’ reimaginations of the classic fables throughout time.

Graduate College student Emma Dove curated the Fralin exhibit, and hoped to spark conversation on the various representations of Aesop’s fables throughout history for educational, entertainment and political purposes.

Dove pulled illustrations from “The Fables of Aesop Paraphras’d in Verse: Adorned with Sculpture and Illustrated with Annotations” — a book of edited fables from 1665 to 1668 — to highlight politically motivated renditions of the fables.

According to Dove’s inscription next to the pieces, the publisher and illustrator — John Ogilby and Wenceslaus Hollar, respectively — involve “pointedly political” references to the English Civil War. History fanatics will appreciate the connection between “Of the Lion and the Forester” and the conflict between the Royalists and the Parliamentarians. The common art amateur who is unfamiliar with the English Civil War might need to do some extra reading.

In the next and most intriguing section of the exhibit entitled “The Moral of the Story,” Dove further explores the iconic conclusions of Aesop’s fables and their political and social implications. “The Supreme Court (The Swallow in Chancery)” from “Aesop Said So” is one such overt commentary on the American political landscape.

Pairing the fable — about a swallow who makes a nest by a courthouse and suffers at the very site where people seek justice — with an illustration of a sword piercing three Acts of Congress artfully reveals the “antagonistic relationship” between President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and the U.S. Supreme Court, according to Dove’s description.

The exhibit is brilliantly thought-provoking, taking on an active role in encouraging viewers’ interpretations of the pieces. Dove includes signs with questions for her viewers to reflect upon the artwork before them. The questions in front of “The Lion and the Mouse” — an interactive pop-up illustration from “Aesop’s Fables: A Pull-the-Tab Pop-up Book” — steer viewers towards considering the dynamics between authors and audiences implicit in the content authors create.

“Why might it be easier for people to identify with animals in this context?” Dove asks on the sign. “Why might children identify with animals more than human characters?”

As “Figure and Fable” moves into identifying Aesop as a historical figure, the exhibit continues to contemplate the roles of authors and audiences in retelling Aesop’s fables, this time, considering how Aesop’s identity influences the morals of his stories. The next section, titled “Figuring Aesop,” includes a brief description that describes Aesop’s life from 620 to 564 BCE as an enslaved person who was freed and became known for his storytelling and wisdom.

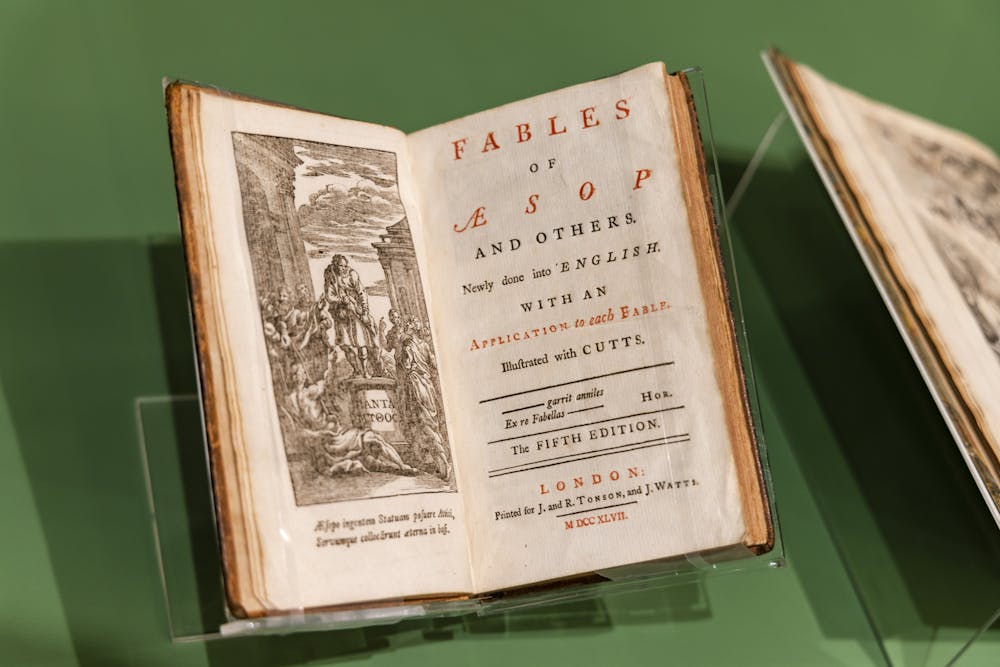

Early depictions of Aesop — such as the frontispiece of “Esopi Appologi Siue Mythologi Cum Quibusdam Carminum et Fabularum Additionibus” published in 1501 — feature darker skin and hunchback.

Classics Asst. Prof Dr. Jackie Arthur-Montagne, an expert in all things Aesop, expanded on Aesop’s appearance and its effects on his fables’ meanings. She explained that many of Aesop’s fables originate not from his storytelling but from before Aesop and ancient Greece, tracing back to Assyria, ancient Ethiopia and ancient Egypt — thus, attributing the fables entirely to Aesop is misleading because he is not the first person to tell these stories.

“You can take the fable away from Aesop…but when you have Aesop, you have the sense of a fable being used to disrupt power structure,” Anthur-Montagne said.

Fast forward three hundred years to 1839, and the frontispiece of “Aesop’s Fables, With Upwards of One Hundred and Fifty Emblematical Devices” completely transforms this look, portraying a light-skinned, thinner Aesop with “a scholarly pose for consumption in pre-Civil War America,” as Dove says in the accompanying description.

“Figure and Fable” surrounds viewers in a comforting blanket of childhood stories as they delve into new territory — the realm of political subtexts in the fables’ modern retellings. The exhibit allows both newbies and experts to explore the evolving balance between creator and audience, the historical usage of fables and the interactive engagement Dove weaves into the story of Aesop and his fables.