Students gathered Friday evening as the Jefferson Literary and Debating Society hosted Dexter Ingram, former State Department official and counterterrorism operative involved in the operations against ISIS. Ingram encouraged students to expand their understanding of national security work, emphasizing service, humility and the importance of diversity and cultural awareness in U.S. foreign policy.

Ingram, who spent years overseas working on counter-ISIS initiatives and counterextremism programs, emphasized that modern national security work extends beyond traditional military pathways. Reflecting on his early career and the unexpected trajectory that led him into counterterrorism, he explained that many national defense careers begin not through rigid planning but by following opportunities that align with their passions.

“I’ve been in the Navy, I’ve worked on Capitol Hill, I’ve worked in the private sector, I’ve also worked at think tanks. I’ve done it all,” Ingram said. “I wasn’t set to one path, but to streamline throughout that was my curiosity, my passion, my connection and really just trying to make the world a better place.”

Ingram began his career as a naval flight officer before working for the U.S. Department of State. He recounted working with multiple Secretaries of State and interagency teams for over 25 years of service, emphasizing the importance of teamwork in national security. Ingram noted that even high-profile missions rely on collaboration rather than ego.

“I want people who don’t make it about themselves. If you do that and you like making a difference and doing things you only read about or see in movies, this is the job for you,” Ingram said.

Second-year College student Kiro Ibrahim said Ingram’s talk had reshaped his own understanding of the field of national security. He stated that many students view national defense as a singular, military-focused path, but hearing real-world missions helped him connect these lessons to his own interest in law and public policy.

“When you say national defense, everybody kind of thinks of one projected way — like West Point … or the military … But he was able to show how it was broader than that,” Ibrahim said. “I’m super interested in law, and this is an area [that is] underrepresented in law or public policy.”

Throughout the talk, Ingram reflected on successes and pitfalls he witnessed across agencies. He described environments where policy and ground realities did not always align — particularly in international settings where cultural competence was essential. He emphasized the importance of treating foreign communities with dignity and recognizing their humanity.

Ingram also discussed the role of vulnerability and personal growth in his career. Recalling his time in flight school, he described being the only student to successfully complete a critical flight exercise despite intense pressure and setbacks. To Ingram, national security is not only about protecting the nation but being able to put yourself in a vulnerable situation to serve others.

“I know CIA agents [who] have done things that would absolutely blow your mind … The service aspect, you’re literally making a difference,” Ingram said. “I know I saved tens of thousands of lives. I don’t know many jobs where you can say that.”

With the goal of connecting young people to national security careers, Ingram founded a non-profit organization, IN Network. Students can access mentorship, internships and training through the organization. He shared that many of his colleagues lead major agencies and that his non-profit organization opens doors for students aged 13-26 who otherwise lack exposure to the intelligence community.

“They got into the job to make a difference, and now they’re hoping to maybe inspire young people to do more. It’s a calling,” Ingram said.

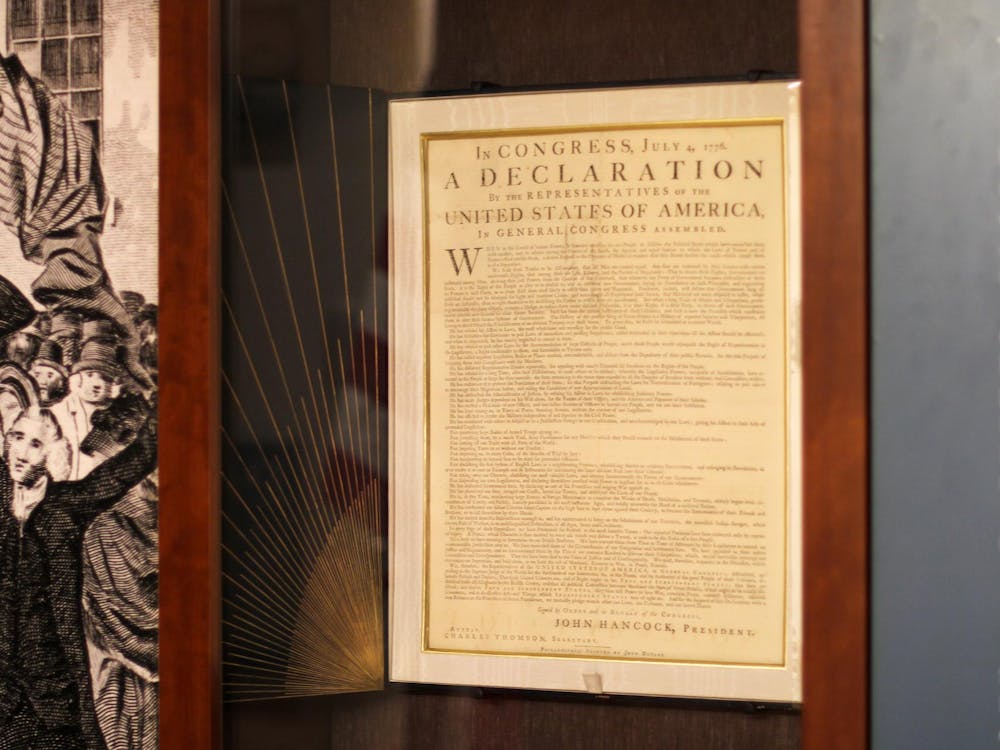

Beyond his nonprofit work, Ingram shared insights from his extensive private collection of espionage artifacts, which includes a myriad of historic intelligence tools. Many of these gadgets and stories are featured in his book, “The Spy Archive: Hidden Lives, Secret Missions and the History of Espionage.” In his book, Ingram uses specific artifacts to explore how the lesser-known details of intelligence work shaped major world events, such as World War II and the Vietnam War.

In discussing the history of intelligence work, Ingram emphasized the value of recognizing overlooked historical contributions. He compared two stories during World War II to illustrate that those with diverse backgrounds have strengthened national security, despite not always having been recognized for their work. He highlighted the contributions of the Cambridge Five, a group of elite British men recognized for their work as secret spies, collecting information from the British government for the Soviet Union.

Contrasting the recognition of the Cambridge Five, Ingram recounted the story of Alan Turing, who helped crack the German naval Enigma code. Turing provided the Allies with intelligence and shortened the war in Europe by an estimated two years. He was unrecognized for his work until the 1980s due to systematic discrimination as he was a homosexual man.

During a Q&A session, students responded enthusiastically to Ingram’s message, asking about Ingram’s experiences working under high-profile leaders. He praised their leadership styles and openness to listening, recalling how his advice was sometimes a factor in decision-making.