What does a film adaptation owe its source material? What if, say, that source material is one of the most famous novels of all time — Emily Brontë’s 1847 novel “Wuthering Heights?” Ever since news broke of director and writer Emerald Fennell’s plans to adapt Brontë’s classic Gothic love story, reactions have been divisive. Many people believe that Fennell owes the original text quite a lot, and have been put off by the modernized costumes, inaccurate racial casting and hypersexualization promised by promotional materials. Now that the movie — released on Thursday — has made its way into the public sphere, it is evident that while some of these twists are eye-catching, they fail to coalesce into something truly visionary.

Fennell has established herself as a director interested in the intersections of sex and death with her previous work including 2023’s “Saltburn” and 2020’s “Promising Young Woman.” “Wuthering Heights” is no deviation from this trend, to both her strength and detriment.

Taking place in Yorkshire, England, “Wuthering Heights” follows the emotionally charged relationship between Catherine Earnshaw, played by Margot Robbie, and her foster brother of sorts, Heathcliff, played by Jacob Elordi. When Catherine was a young girl, her father took Heathcliff in as his ward. This status distinction shapes Catherine and Heathcliff’s bond as they grow up and fall in love. Heathcliff is perceived by multiple characters to not be truly “good enough” for Catherine, and he runs away after Catherine is proposed to by their neighbor Edgar Linton, played by Shazad Latif. Despite this, the two cannot stay away from each other, and twisted romantic entanglements and backstabbings with the neighboring Lintons ensue, ultimately ending in tragedy.

A jarring opening scene — in which townspeople become aroused at the sight of a public hanging — immediately sets the tone for the rest of the film. The line between love and horror is continuously blurred, exemplified in scenes such as Isabella Linton — Edgar’s ward — chained at Heathcliff’s feet after the two marry. This tactic is shocking and initially engaging, but it ultimately rings hollow.

For instance, the first sexual encounter between Heathcliff and Catherine comes after they watch two servants hooking up in the barn. While the film makes it evident that there is a building attraction between Healthcliff and Catherine, not enough time is spent on their own relationship to justify their sexual catalyst being two other people, and the moment ends up feeling a little removed from their intimacy.

Furthermore, more important plot points — Catherine’s marriage to Edgar Linton and her subsequent affair with Heathcliff upon his return — are sped up and seen through montages. These montages are not entirely bad parts of the film, as they are visually stunning and allow Fennell to cover more territory in a condensed amount of time. However, Robbie and Elordi do not capture the intensity of their love affair in their moments of dialogue. Iconic lines like “whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same” feel too calm, because attention throughout the film seems to be more focused on the idea of sex itself and not the relationship between the main characters.

This lack of faithfulness to the source material also arises in the fact that Fennell cast a white man as Heathcliff. Although Heathcliff’s race is never specifically stated in the novel, it is heavily implied that Heathcliff is not white. Ignoring this layer of complexity — while simultaneously casting people of color as Linton and Catherine’s paid “companion” Nelly Dean, played by Hong Chau — only serves to flatten out the intricacies and politics of the original text into a story solely about romance.

Instead of the most interesting relationship being between Catherine and Heathcliff, it ends up being between Catherine and Nelly. Nelly is only a few years older than Catherine — thus, she grows up just as affected by Catherine’s father’s violence and alcoholism. Yet without Catherine’s ability to marry someone wealthy and escape her class station, Nelly is forced to stay by her side, resulting in the two women having a toxic, sisterly bond all throughout their lives.

Throughout the movie, Chau depicts Nelly’s love and hate for Catherine with almost imperceptible shifts in expression and quietly reserved anger. Catherine is awful to Nelly — in one scene, she tells Nelly to leave and find other employment with a complete lack of regard for the fact that Nelly has nowhere to go. Nelly is awful back, inadvertently causing Catherine’s death after ignoring her sickness and not realizing it has developed into septicemic plague. Still, their last moment together is more powerful than any between Heathcliff and Catherine, because Nelly and Catherine continuously saw each other at their worst and yet loved each other nonetheless.

Regardless of its shortcomings in characterization and storytelling, the film is very beautiful, with the music being especially noteworthy. The score by Anthony Willis is gorgeous and haunting, perfectly complementing various shots of rainy Yorkshire Moors. Charli xcx contributed an album of original songs, such as “House,” which plays at the beginning of the film and was also released as a single in 2025. The song captures the horror and claustrophobia of Catherine’s childhood through eerie instrumental distortion as the lyric “I think I’m gonna die in this house” is repeated, proving that modern spins on classics can work if the emotional core of the story is maintained.

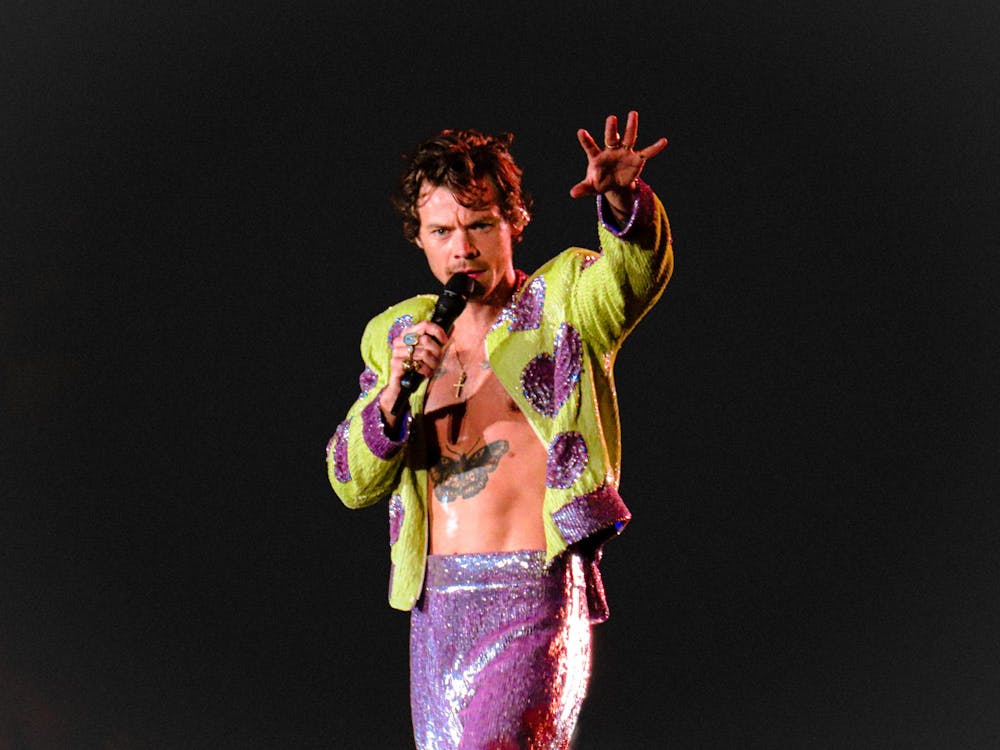

Without the unique score capturing the internal turmoil of the characters, though, the movie would feel even more like an exercise in style over substance. This is in part because of the costumes, which are colorful, striking yet not historically accurate at all. A lack of historical accuracy is not inherently problematic if it is clear that is not what the director is attempting to do. Fennell has made that clear by virtue of the costumes being so extravagant, intentionally breaking with the period of the film to convey her unique artistry. Corsets, latex, transparent puffed sleeves and more are paired together in every color of the rainbow. However, Robbie’s acting is not strong enough to match the flashiness of the costumes, and as such she is often overshadowed by her own dresses.

Realistically, Emerald Fennell does not owe Emily Brontë that much in terms of beat-for-beat replication. A film is not a novel, and directors should be allowed to imbue a story with their own vision. Plenty of people will no doubt be driven to read the book after watching this movie, and that alone should be seen as a great success. Nevertheless, after those said people read the book, they might come to the conclusion that Fennell’s version pales in comparison.