Few high school sports have a death toll. Of course, freak incidents happen — a wayward skate, or a bad tackle. But there is only one high school sport whose athletes are at risk well before any practice or game begins. That sport is wrestling.

This is not hyperbole. Just ask the family of Ryan Estrada, a 16-year-old from Michigan found dead while trying to drop 15 pounds to compete in a lower weight class. Or of 18-year-old Damien Mendez, who collapsed while running outside his school in Kentucky in a sweatsuit. Or of Freddy Espinall, a 16-year-old who suffered a medical emergency during a wrestling practice just a town over from me in Peabody, Massachusetts.

From the little you can find online to read about these young athletes, two things are clear. First, they each led vibrant lives, leaving communities to mourn their loss. And, second, they all died as a result of widespread weight cutting made possible by the institutional negligence baked into the very DNA of high school wrestling. With no systemic policy shift at the high school level, stories like those above will remain all too common. But the Virginia wrestling team and NCAA policies show us that they do not have to be — and we do not have to wait for tragedy to strike the Charlottesville High School team itself to make changes.

It occurs to me that many readers may be unfamiliar with what weight cutting even is. Wrestling, like some other sports, divides athletes into weight classes. In combat sports like wrestling, where any advantage in size and strength is a welcome one, weight can be a major determining factor in success. At the highest levels of combat sports, fighters spend as much of their time and energy focused on weight management as they do on improving their martial arts ability. Fighters in the UFC, for example, typically hire a whole team of nutritionists and coaches just to manage their weight cuts.

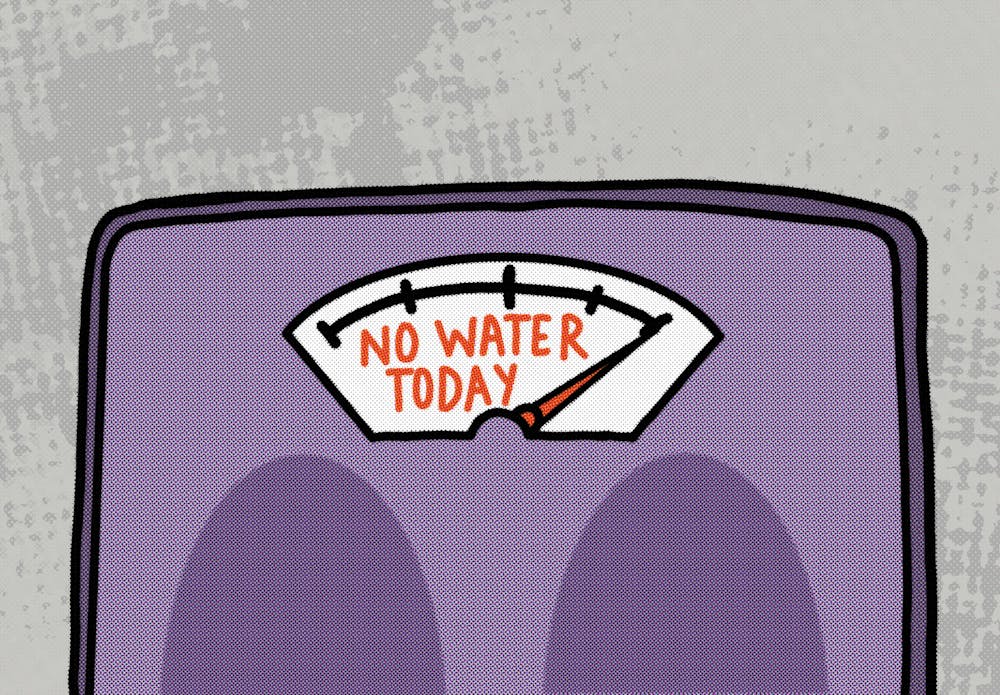

Of course, the term “weight management” itself paints a misleading image — one worth correcting. This is not opting for salad over a burger in preparation for a beach vacation nor is it having one drink instead of two on a night out with friends. No, weight cutting is tactical, purposeful dehydration. More often than not, what is being cut is not fat but water. An athlete drops as much water weight as possible, maintaining their muscle mass, to step on the scale at as low a weight as they are able. Before 1997, there were no real regulations on athlete weight management at any level of combat sport.

Where high school wrestling finds itself today, collegiate wrestling found itself just over 25 years ago. In the 1997-98 NCAA season, three athletes, Billy Jack Saylor, Jeff Reese and Joseph LaRosa died and died the same way — organ failure after collapsing at wrestling practice. In order to better understand how college wrestling reckoned with that tragedy, I sat down with Virginia Wrestling Head Coach Steve Garland.

Coach Garland was a second-year wrestler at Virginia during that season in 1997. The Virginia team had just returned from a road trip that saw the grapplers compete with schools across the country. The first thing Coach Garland remembers hearing was not how Reese died, but that the NCAA would be giving each wrestler a seven pound weight allowance for the rest of the season — relieving the remaining wrestlers from the clear strain on their health caused by weight cutting. Reese, who died in December of 1997, was the third dead collegiate wrestler in three weeks.

After 1997, the NCAA enacted sweeping reforms — some of the first of their kind. The new rules impacted every part of a wrestler’s year. On paper, the NCAA wrestling season begins in November. But as any wrestler will tell you, the season starts well before that. The reforms require athletes to undergo mandatory weight certification in late August. Here, athletes have their body composition, weight and hydration levels recorded — the last being a crucial metric to ensure that athletes have not already begun to cut weight in an attempt to obscure their natural weight. Once these are recorded, the NCAA gives an athlete the range of weight classes they are certified to compete in. The NCAA then routinely checks athlete body composition in the weeks leading up to the season.

If it is found that an athlete has lost more than 1.5 percent of their body weight per week — the number deemed safe by the NCAA — or if they fail a hydration test, they risk being unable to compete. Coach Garland said that the rules and reforms “transformed” college wrestling after 1997. A far cry from the wild west weight cutting days of the 1990s, the Virginia squad has a dedicated team of nutritionists and sports scientists who ensure that the highest standards of athlete safety are met. In the 28 wrestling seasons since 1997, there has been one confirmed weight cutting-related death across the NCAA. This is still, of course, too many, but it is a stark contrast from the tragedy in 1997.

The lessons from 1997, though brutal to learn, are clear — battling weight cutting requires systemic change. Yet, they are lessons that high schools have failed to grasp. The National Federation of State High School Associations, the principle governing body behind all high schools sports, has but one article on weight cutting. It is less than 1000 words. Don’t let the title fool you. Despite being titled “Rules in Place to Guard Against Weight Cutting in Wrestling,” a reader anticipating to find rules will be sorely disappointed. Instead, the Federation describes the “ideal program,” that “discourages” excessive weight loss. There is no talk of requirements, nor a system in place to enforce their ideals. And it is not as if the Federation is ignorant — they mention the pre-season weight certifications as “a sensible alternative to dehydration.” No, the NFHS is not ignorant, nor impotent. Yet, their lack of action may leave some with an impression of the contrary.

And their inertia is felt by every high school wrestler across the country. My high school team was sharp enough to have a preseason weigh-in. Unfortunately, we were dull enough to have it just one week before our first meet. As a result, the rest of the team and I cut all our weight throughout November and early December, well before the season and formalized weight tracking began. At six foot and 160 pounds, I was able to trick the scale into thinking I walked around at 140 — 20 pounds lower than my natural weight. By manipulating my weight prior to weight certification, I was able to get certified in the 132 pound weight class.

In their ideal program, the NFHS suggests that “minimum body fat should not be lower than seven percent for males or 12 percent for females.” I ended that season at 129 pounds and 5 percent body fat. All I got was a high-five from a teammate coming off the scale. The NFHS’s inertia created a winter where I went to bed thirsty each night. It created a culture of saunas and sweatsuits.

My experience was hardly rare. The institutional inaction by NFHS is felt right here by young athletes in Charlottesville. The Charlottesville High School program has just above 20 grapplers across their junior varsity and varsity programs. This number grows significantly when you take into consideration the athletes in junior high and youth programs. All of these wrestlers, some barely older than 10, enter a sport where the sort of weight cutting practices performed by professional fighters are not uncommon — only youth athletes more often than not lack any supervision. I was never taught how to cut weight. I was just punished when I missed weight. This perpetuates a system where athletes are encouraged, implicitly and even explicitly, to cut weight by any means necessary.

Change is rarely easy and this change would be no exception. I do not doubt that enforcing the sort of preseason weight certification process that occurs at the NCAA level would be difficult for secondary schools. But it would be far from impossible. After all, high schools already have the scales required to run a preseason weight certification — they just lack the gumption to use them earlier than they do. Their hesitation rests on grounds not unfounded. For the most part, high school sports are just an opportunity for kids to socialize and stay in shape. Students join teams on a whim. As a result, actions that effectively force wrestling season to start early in fall and even into late summer may even drive down the popularity of the sport. However, I refuse to believe it would be worse for the sport than kids dying.

This alone will not solve the problems plaguing high school wrestling. My accusation is a genetic one — it is aimed at the core of the sport. As viewed by the intense expectations of weight which wrestling necessitates, negligence seems to me a part of the DNA of high school wrestling. Study after study shows the link between weight-based sports and disordered eating. Merely weighing athletes earlier in the season does not break this link. It takes comprehensive, cultural change to do that.

Luckily, this is a reality Coach Garland recognizes. Garland takes issue with applying the term “weight cutting” to the Virginia team.

“It’s not cutting weight. It is not ‘the weight cut’ — that is UFC stuff. College wrestling should be [a] lifestyle,” Garland said.

And for Garland’s wrestlers, that lifestyle is one where athletes are disciplined but also highly educated on proper nutrition. Garland touts that his athletes are rarely seen without a gallon jug of water. As he reminisces, this would have never happened in the 1990s, an era where weight cutting was synonymous with dehydration and short term results. By embracing the NCAA reforms, Coach Garland has worked to create a team of athletes invested in sustainable healthy practices.

This healthy mindset needs to take hold at more than just a college level, and the University can play a role. High school athletic programs measure success primarily through two metrics — state championships won and college athletes produced. Sending athletes to the Virginia team, a division one program, reflects well on the high school program that produced them. This gives the University leverage in how those programs operate. They may not realize it, but the team has the opportunity to spread their team culture to high schools across the country. Send the schools of would-be prospects a simple message — you want to be recruited by us? Play the game our way. Institute the preseason checks that are routine at the University program. This would do more than just create a pool of prospects versed in the culture celebrated at the University — it would save lives.

Dan Freed is a senior opinion columnist for The Cavalier Daily. He can be reached at opinion@cavalierdaily.com.

The opinions expressed in this column are not necessarily those of The Cavalier Daily. Columns represent the views of the authors alone.