As part of ongoing efforts this fall, University researchers have published a study demonstrating that previously depleted oyster reefs can be restored to the conditions of original populations in only six years. A culmination of over 15 years of work, this research was done in collaboration with the Nature Conservancy, a global environmental nonprofit organization based in Virginia.

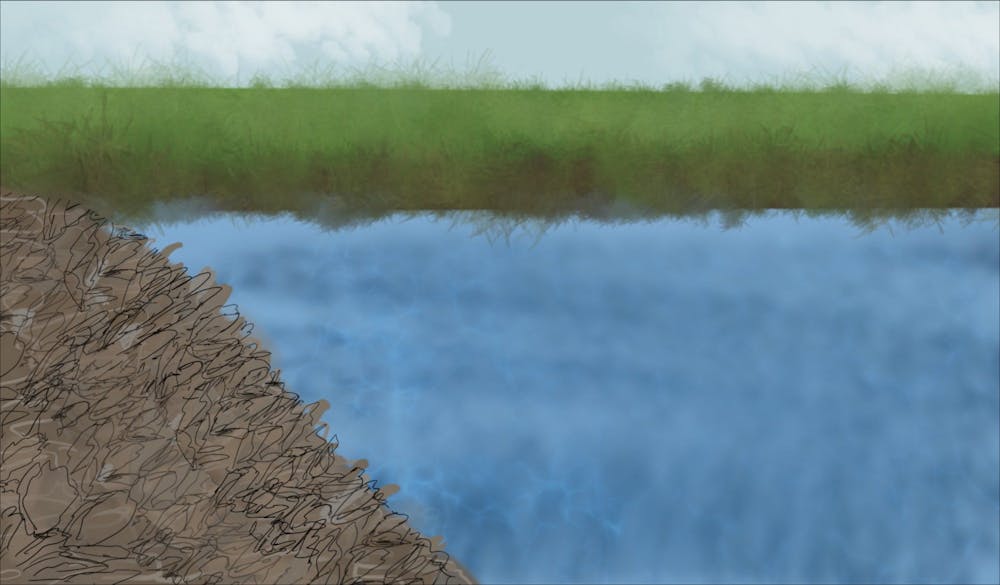

Oyster reefs consist of colonies of shells from living and nonliving oysters that fuse together and form on hard substrates, such as stone. However, oyster reef populations have been declining due to erosion from development, nutrient pollution, overharvesting and disease.

Bo Lusk, a scientist at The Nature Conservancy’s Volgenau Virginia Coast Reserve, emphasized the importance of oyster reefs in providing habitats for other species, such as shellfish and small fish. Additionally, oysters filter and remove excess nitrogen from the water to pump it back into the atmosphere through denitrification.

Oysters can also protect human communities by decreasing shoreline erosion.

“[Oysters] really work pretty simply as a living breakwater,” Lusk said. “If the height of the water is right, when you have storm waves rolling in towards the shoreline, the waves will break on that oyster reef instead of breaking on the shoreline.”

The organization started oyster reef restoration in 2003 and has been monitoring them since 2005. At 16 sites in Coastal Virginia, random samples were collected from quadrats at 70 intertidal reefs during low tide. They were then brought back to the lab for counts of oysters as well as other materials and organisms, such as dead shells, crabs or mussels, all of which serve as indicators of how the process of restoration is proceeding.

“[The analysis of the quadrants] has been done annually with 15 years of good data for this report,” Lusk said. “That's unique because, in the oyster restoration world, we're lucky if we can get funded to do that type of monitoring, even just for two or three years. To be able to follow this for such a long period of time and have such a huge amount of data to support these conclusions makes the study pretty important and really unique.”

The Nature Conservancy has been collaborating with scientists from the University for decades through the Virginia Coast Reserve Long-Term Ecological Research program, such as Rachel Smith, a NatureNet Science Fellow and postdoctoral researcher. Smith, along with Asst. Prof. Max Castorani and Lusk, are co-authors of the study.

“[The Nature Conservancy] knew they had this monitoring data set and they also already had this existing collaboration with Max,” Smith said. “My role was to sort of bridge those two sides and work together to interpret a lot of the monitoring data they’ve been collecting.”

Smith, Castorani and Lusk found in their research a six-year timeline for when restored reefs began to match natural ones, helping to narrow down the time periods in which future researchers should sample the reefs.

Smith is working on an additional study to understand why restored reefs either succeed or do not succeed in some places. Smith and Castorani explained that possible factors could include wave fetch, which is the distance over water that wind blows in a single direction, water residence time and reef elevation. Castorani noted that the water quality of the 70 intertidal reefs also played a role in the outcome.

“If you were to compare the place where we worked with certain tributaries of the Chesapeake [where there is more development], those tributaries have more challenging water quality concerns,” Castorani said. “That can compound the difficulty of restoration in the sense that if they build the reef, perhaps there's more uncertainty about whether that reef is in an environment in which it will thrive.”

Oyster reef elevation is not only important for shoreline protection, but also for oyster survival. If a reef is built too low, especially in saltwater ecosystems like Coastal Virginia where predation is high, oysters cannot survive to build the reefs. On the other hand, if reef elevation is too high, oysters can be out of water too often and not get enough food. Sea-level rise over time has also made certain areas too deep for oysters to grow.

Oyster castles are concrete blocks that have been modified to function as a living reef, allowing oyster larvae to attach and grow. By using man-made substrates such as oyster castles, reefs can be constructed to a proper elevation.

“With just a little bit extra height, suddenly our oysters will survive and that reef will continue to grow up,” Lusk said.

This study has influenced oyster restoration projects all over the world, according to Lusk. Additionally, local communities in Coastal Virginia have gotten involved in conservation efforts according to Jill Bieri, director of the Volgenau Virginia Coast Reserve.

“In order to achieve our restoration goals, we have to be involved and connected to the community,” Bieri said. “We can take them out and they can actually put their hands on some of this oyster restoration. They can put substrate down on the bottom that's growing oysters and that's pretty powerful for people to be involved in the effort.”

According to Bieri, this research can mitigate the impacts of rising sea levels on rural, coastal communities using oyster reefs as a “nature-based” solution.

“Our coastlines are using these nature-based solutions,” Bieri said. “I think it's really powerful what we're demonstrating at the Virginia Coast Reserve in terms of nature-based solutions and resilience.”