The NCAA basketball tournament raked in over a billion dollars in revenue last year, and this money is used to reward the conferences that made the best showing. There are many ways that the money is distributed to the conferences, but the only one shaped directly by tournament performance is known simply as the “basketball fund.” There is a lot of money to be won, for smaller conferences especially, but most teams in the tournament come from power conferences like the ACC.

This year, the ACC placed 9 teams into the NCAA tournament, including top-ranked Virginia after a 31-2 season and title win against North Carolina in the ACC tournament.

Athletic success can garner attention for a school through substantial media exposure, and the University usually benefits from high performance. A big run from Virginia would certainly be significant for the University community, but ultimately, tournament revenue is not as substantial as it might seem.

Where the NCAA gets its funds

The funds generated from the NCAA tournament dwarf those from the regular season. Whereas conferences receive money from television marketing and ticket sales over the course of the season, the NCAA is the sole distributor of revenue for the Big Dance. Last March, television and marketing rights came out to $821.4 million and ticket sales to $129.4 million. The television revenue is largely drawn from the league’s 14-year contract with Turner Broadcasting, estimated at around $10 billion.

The March Madness tournament is unique from other competitions such as football bowl games and the College Football Playoff because the NCAA has the exclusive rights to all television coverage and ticket sales during its tournament season. During the regular season however, conferences themselves are the ones striking basketball deals with providers.

“Conferences make deals that allow every member a certain amount of regular season games on a particular channel, but the providers maintain leverage such as what time the game airs,” said Randy Meck, former Dartmouth assistant athletic director.

Regardless, the television coverage for games in the tournament is far more important than regular season games. More people watch during March Madness, and the potential exposure a school can get from a Final Four run is huge. Just think of George Mason’s insane run from first four to Final Four in 2006, which brought in a lot of extra revenue for the Colonial conference and put the school in the national spotlight. Teams that go farther into the tournament enjoy better recruitment, an increase in enrollment and more prestige. As for revenue, though, big conferences tend to split up the money evenly, so there is not as much fluctuation as smaller schools experience.

“It’s good for the ACC for someone to make it to the Final Four, and if you get two or three teams, that’s huge,” said Steve Pritzker, University Athletics chief financial officer. “But from a budget standpoint it doesn’t move the needle significantly; it takes time for all the funds to come in.”

How the basketball fund operates

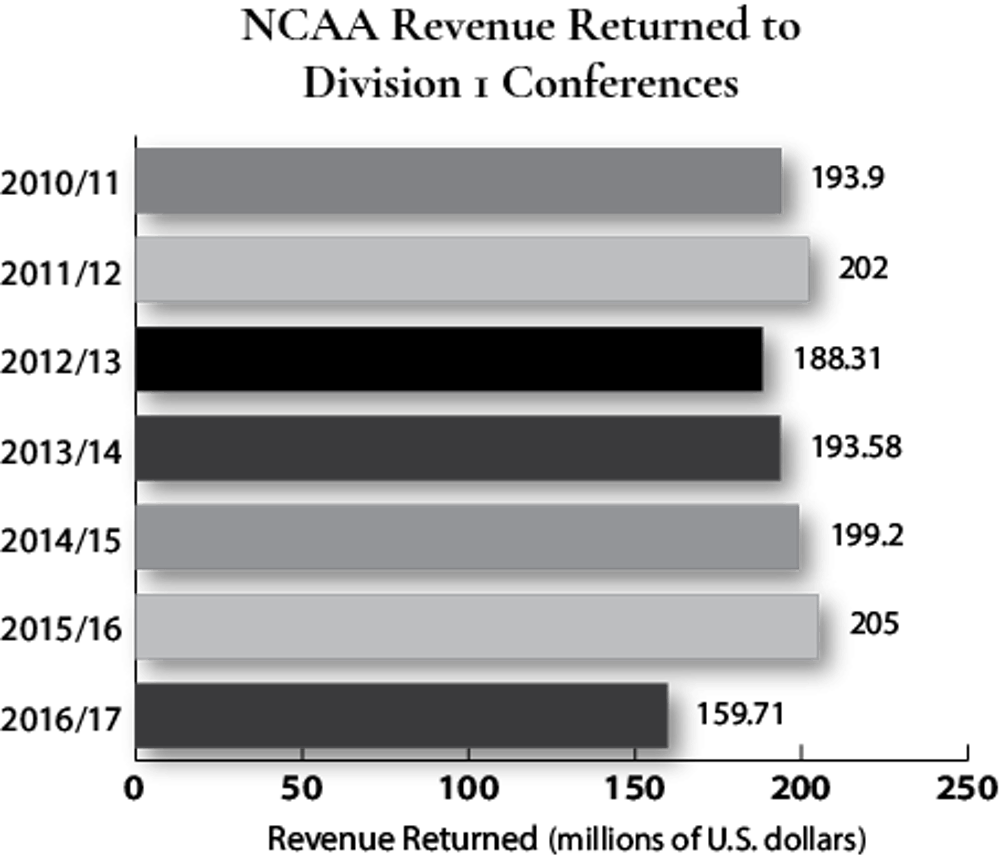

The basketball fund is the largest form of distribution to the conferences, a pool which was worth around $220 million in 2014 and was awarded to teams based on their performance by means of “units.” The units correspond to the number of available slots there are in the bracket — from first four to Final Four — and every game a team plays in the tournament earns them one unit for their conference. Other forms of distribution are evenly spread out over the entirety of the NCAA, and include money towards scholarships, team expenses, Division II and Division III budgets and student assistance.

There are 132 units available in the tournament, corresponding to the initial 68 slots in the bracket, as well as the open slots in the further rounds. While the units stack up as a team makes it farther, there is no increase in the unit price the further a team goes.

Each unit for 2018 is worth $273,000, and the units will increase in value as the full unit is distributed over six years.

An important matter to consider when examining NCAA funding is that the money accumulated from a tournament run does not go to the institution directly, but to its conference.

“Basically all schools in the ACC will get the same amount money from the conference, regardless of how well their team does,” Meck said.

The ACC conference received $30.6 million from 18 total units in the 2017 tournament. The University gained two units last year equaling $3.4 million for the conference, but the way the distribution works, the $30.6 million was divided by the 14 schools to be split as $2.19 million per school.

Revenue sharing and future distribution

While the money that comes in from the basketball fund does have an impact, even the most successful basketball programs make around the same amount of money as a mediocre football team. Football ticket sales and ad revenue still dominate the sports world. However, many schools in the smaller conferences do not have football teams, so the basketball fund brings in a much larger portion of revenue.

“Football ticket sales and ad revenue still dominate the sports world,” Meck said. “So Virginia making a bowl game this year will probably still net more money than a run to the elite eight.”

The ACC can function very well off of the revenue sharing system, meaning that whatever the sport, funds come directly from the overall performance of the conference. The more money that is allocated to the conference, the better every conference team can do. Even though the University might not have the best football team, it makes up for it during basketball season.

“Revenue sharing within the conferences may not seem fair to a team that has both a great football and basketball team,” Meck said. “But you have to look at it this way — if the overall conference is better, it not only helps recruiting for all members, but allows for more bowl revenue and NCAA tournament shares for the entire conference.”

In the future, there will be another point of distribution made up of excess projected revenue for teams to compete for, much like the basketball fund. However, instead of competing for athletic success, the determinant of revenue for conferences will rely on the academic success of students. This is part of a mission to ensure that student-athletes are getting a meaningful education, while also serving as an alternative to methods such as player salaries. This new distribution of revenue will be implemented in the 2019-2020 season, and will draw more upon tournament revenue.

“The movement to reward institutions for academic success and not just competitive success is already underway,” former University Athletic Director Craig Littlepage, said. “It should make for a better system.”

Outcome of tournament performance

Money from the March Madness tournament regularly goes towards salaries for athletics staff, improvements for facilities and team programs, paying for operations costs, travel and outreach for recruiting new talent. Recruiting is also impacted by a team’s high performance in their previous season, and maintaining a competitive team every year is crucial so as to not fall behind in the long-term recruitment process.

Other benefits of impressive tournament performance include the rise of merchandise sales, donations from alumni and increased offers from television marketers.

Some might argue that the excess revenue from tournament play should go directly to the players as a salary. This issue has been debated for years and has recently been reignited by the NBA’s consideration of eliminating the “one and done” rule, which mandates that players spend at least one year in college before transitioning to the NBA. The argument is that players could be enticed to stay in college if they were to be paid for their performance, rather than waiting another year until the draft.

There are two prevailing arguments against providing players compensation. The first is the precedent that paying amateurs would set, and the second that top athletes are already receiving aid via scholarships. In reality, there are only a select few players capable of making the leap straight to the NBA, and athletic experts believe that the greater benefit lies in supporting student-athletes to strive for excellence and success in all aspects of life.

“We’re trying to help our athletes be leaders on and off the field and represent the University well,” Pritzker said. “We want an overall successful portfolio that looks good across the board.”

With Virginia as the No. 1 overall seed and two other teams second seeds, the ACC is looking like it might top the conferences again in units this year. The support from fans and the University community nationwide is often the driving force behind more revenue and contributes more to the success of the team than the regular distribution of the basketball fund.

“No financial value can be placed on the benefit of the program,” Littlepage said. “And there’s no way to market a university better than a few nights in March.”