Researchers at the University are working to tackle the question of why boys get diagnosed with autism four times as much as girls. A pan-university project — Supporting Transformative Autism Research — coordinates several research projects on autism and innovative models for intervention at the University to address issues similar to this and create better diagnostic tools to provide proper care for both genders.

These studies involve researchers from various fields such as the neurology department, Data Science Institute and the psychology department. The STAR initiative is encouraging collaborations between researchers of various areas to tackle different aspects of the problem and establish the University as a powerhouse for autism research.

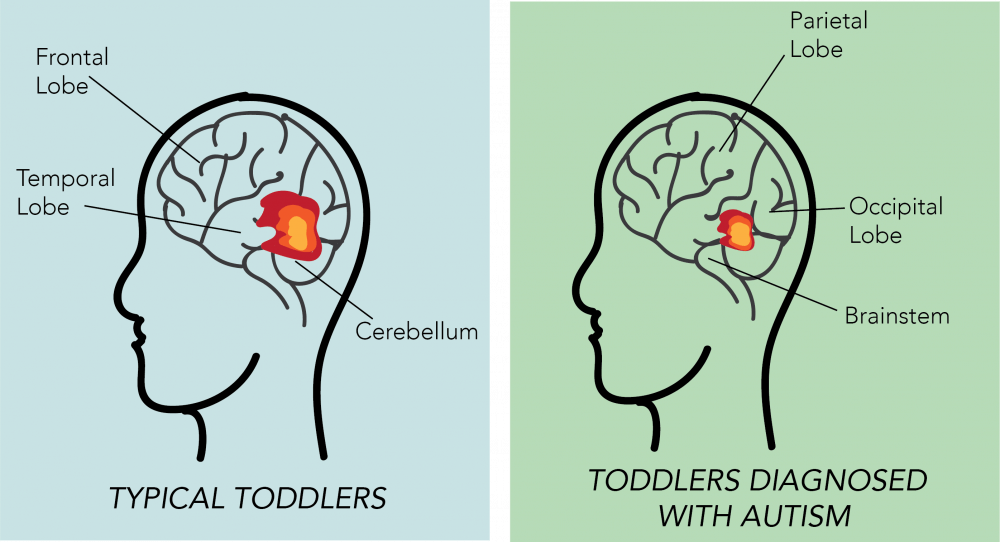

One particular project led by Kevin Pelphrey, Harrison-Wood Jefferson Scholars professor of neurology, is trying to understand the differences between the development and structures of brains of female and male children with autism. Funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, this project is a part of the National Institute of Health’s Autism Centers of Excellence Program. It bridges researchers across several universities — such as the University of Virginia, the University of California, Los Angeles and the Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C.

Since the beginning of the formal diagnosis of autism by Dr. Leo Konner at Johns Hopkins University, it has been noted that boys are more likely to develop autism than girls. Although boys are generally at a greater risk for brain disorders, Pelphrey said that this reasoning is not sufficient to explain the wide disparity in autism diagnosis. The lack of information about autism’s manifestation in girls means that many are never diagnosed and miss out on beneficial interventions.

One of the factors to consider for this disparity are the biological differences in hormones and genes between different genders. This is a plausible explanation because researchers currently have identified around 70 genes linked to autism, according to Pelphrey, and autism tends to run strongly in families. Another factor to consider is that the diagnostic procedures for autism itself might be gender specific and faulty when diagnosing girls since the procedures were developed with boys.

Pelphrey believes that the gender disparity in autism diagnosis is most likely a mix of both biological and diagnostic factors and hopes to better understand why these differences occur. “We want to start developing measures targeted towards girls because they have been understudied and under resourced in terms of what is available for them,” Pelphrey said.

With a network of universities collecting neuroimaging data, there is a growing importance of data science for processing the large amounts of data in research projects such as these. John Darrell Van Horn, professor of psychology and data science, contributes to the computational aspects of this research project.

“Technology is always rapidly advancing to be able to get more data in space and in time and that has some very important computational implications for how you deal with that data,” Van Horn said.

Van Horn also collects data on demographics and neurophysical measurements to perform massive joint analysis in order to understand how the brain in autism may be functioning. A copy of the data the lab at the University collects and processes is sent to the National Database for Autism Research at NIH in Bethesda, Md. Van Horn hopes to use this data to better understand why boys get diagnosed with autism almost four times more than girls and re-standardize the autism diagnostic process for girls.

Current methods to diagnose autism include observing the child’s behavior, performing cognitive assessments to learn about the child’s problem solving and language skills and interviewing the caregiver of the individual with a focus on social communication skills and repetitive behaviors. Pelphrey hopes to find a biological marker of autism and add brain-based measurements to this assessment to make it more accurate.

The STAR initiative also supports several other research projects to develop new assessment tools to diagnose and assess the symptoms of autism. Micah Mazurek, director of the STAR initiative, associate professor of education and clinical psychologist, is currently working on a project to validate a measure that has been developed to diagnose autism using eye tracking.

Additionally, Mazurek said her team is building a “model called ECHO to train community-based providers in being able to recognize symptoms of autism and provide best practice care for children with autism and their families.”

Overall, the STAR initiative has funded 11 pilot studies over the past year and hopes to continue fostering research studies focused on autism.

The end goal of this research is to make recommendations to clinicians about how to diagnose more accurately and tailor their treatments and therapies to autism more appropriately, said Van Horn.

“In general, we want to develop U.Va. as a go-to place where people look for information about brain development, autism and how best to move kids on a path towards optimizing their outcomes and abilities” Pelphrey said.