Earlier this month, Georgetown University announced it will give preference in admission to descendants of slaves who were sold to help fund the school. When the Jesuit Order founded Georgetown University in 1789, members decided the school would not collect tuition from its students. However, Georgetown’s property included multiple plantations and the slaves who worked on those plantations. In 1838, two Jesuit priests, who had both served as president of the school, helped pay off university debts by selling 272 slaves for approximately $115,000 — the equivalent of $3.3 million today. Like Georgetown, the University’s history is closely tied to slavery, and students and administrators continue to discuss how this past should be recognized.

Slavery’s history at the University

History Prof. Kirt von Daacke, co-chair of the President’s Commission on Slavery, said several dozen slaves participated in the early construction of the University’s grounds.

“[Slaves] terraced what is now the Lawn,” von Daacke said. “They shaped the landscape before [construction] started. They then worked in the various brickyards nearby, where they actually dug clay, shaped the bricks and worked at the kiln. In some cases, they may have even hauled those bricks back to the University.”

As construction declined after the University’s opening, the number of slaves hired by the University began to taper off. However, approximately 90 to 100 enslaved laborers remained to live and work on Grounds. During this period, most enslaved people were owned or rented by professors and administrators of the University.

“The professors at U.Va. quickly purchased slaves,” von Daacke said. “Some of them even went on to purchase plantations and farms in the county — some became significant slaveholders in their own right.”

University officials maintained a detailed record of slave ownership through those professors’ wills and deeds. However, the University did not maintain detailed records of the slaves it employed. Often, the records kept by officials referred to the appropriation of a certain amount of money for the help of “hands,” leaving out details such as names, ages and genders.

Despite the lack of records, prior to the Civil War, slaves ran and maintained the University on a day-to-day basis. In a single day, one enslaved laborer could be responsible for cleaning approximately 20 rooms, working in a dining hall and running errands for students, such as fetching books or supplies.

“The first person a student likely saw every morning was an enslaved person bringing a bowl of water and stoking the fire,” von Daacke said. “These are the people doing the cooking, cleaning students’ rooms — really every aspect important for student life was managed by slaves.”

Is Georgetown a blueprint?

In the early 2000s, students at the University became interested in the University’s history with slavery. Prompted by student interest and the formation of the Memorialization for Enslaved Laborers, an organization that advocates for the creation of a slave memorial on Grounds, President Teresa Sullivan’s administration created the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University.

Von Daacke and Dr. Marcus Martin, PCSU co-chair and vice president and chief officer for diversity and equity, work with the commission not only to acknowledge the University’s history with slavery, but also to repair its wrongdoings to the best of their abilities.

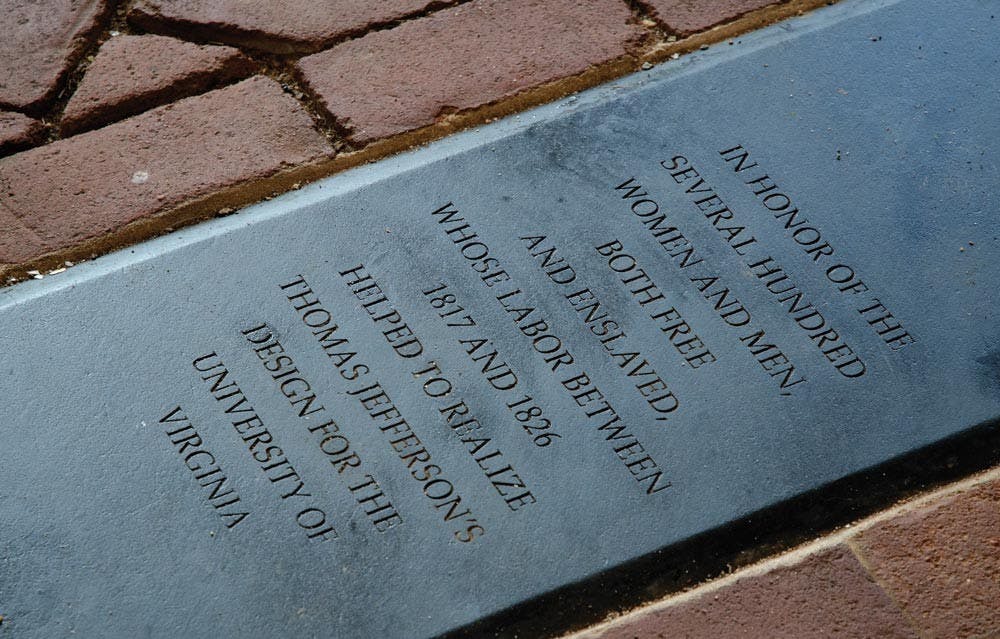

“Acknowledgement is the first step in the process of repair,” von Daacke said. “We wanted our acknowledgement to be a process of reinscribing the story of slavery back onto the landscape in powerful ways.”

Since the commission’s inception, it has focused on renaming buildings and further detailing the lives of several enslaved laborers at the University. For example, Gibbons House was named after William and Isabella Gibbons, a husband and wife enslaved by different professors at the University during the mid-19th century. Additionally, the commission published a map which leads participants on a walking tour of Grounds to areas where enslaved laborers greatly influenced construction and daily life.

Since Georgetown’s announcement earlier this month, members of the University community have asked whether it is practical to enact a similar policy on Grounds. Von Daacke commended Georgetown’s recent efforts to reconcile its history and stressed the fact that the University has developed and is continuing to develop reconciliations of its own. However, he said the University is governed by state law which does not provide the same freedoms as those enjoyed by private universities.

“We are, as a public university, constrained by two 1999 court decisions in the Fourth District regarding using race as a factor in admission,” von Daacke said.

Additionally, Georgetown benefitted from an extremely detailed bill of sale, which allowed the descendants of the slaves sold in 1838 to be traced relatively easily. Since the University contracted labor from neighboring plantations and contractors who personally owned enslaved people, the University’s records rarely include discernable information that could be used to track descendants.

The road to repair

MEL President Diana Wilson, a third-year College student, stressed the importance of educating the entire student body.

“Once the University community is finally aware of this history, we will be closer to becoming the strong and united community we have the potential to be,” Wilson said in an email statement.

MEL has worked since before the creation of PCSU, leading initiatives such as the Memorial Design Contest.

“Our efforts then fostered University action such as voting to create a memorial on Grounds, sending the statement of regret in 2007 and establishing PCSU,” Wilson said.

Third-year College student Weston Gobar, political action advisor of the Black Student Alliance, voiced his support for the commission and steps taken so far, but said he wants to see a more public display of acknowledgement and repair.

“The University is taking important steps to acknowledge its history,” Gobar said. “However, a lot of the plans U.Va. has are long-term solutions. Right now, I would like to see more public affirmation, more things that connect students directly to the history of slavery at the University.”

Gobar said he appreciates statements from administrators as well as the few classes offered to students on the topic. However, he said there is a lack of student knowledge about these offerings as well as memorials, such as the slave graveyard situated near Gooch-Dillard housing.

“Right now, students can go four years and never think critically about the history of slavery at the University,” Gobar said.

Von Daacke said the commission wants to expand its work to include projects that cultivate meaningful discussion, and through that discussion, meaningful action. He also offered a new perspective to critics of the commission’s work.

“You have to look at what we’re doing as a process,” von Daacke said. “The judge of the Commission’s engagement in a process of acknowledgement, reconciliation and repair will be what we’ve done when we’ve finished our work. If you look at how the landscape will have changed by 2019 or 2020, I think that will be clear.”